Spinal ATRT and Radiotherapy Case Report in an Adult Man

A rare case of spinal atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor is presented in an adult man after presenting with neck pain and bilateral upper extremity paralysis.

ABSTRACT

Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (ATRT) is usually seen in children and is usually located intracranially; it generally has a poor prognosis. Due to this tumor’s rarity and the lack of randomized controlled trials, it has been challenging to define optimal therapy and to make treatment advances. Treatment options are surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.1 This is a case report of a man with spinal ATRT, aged 44 years, who was treated with radiotherapy.

Introduction

Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (ATRT) is a malignant embryonal tumor of the central nervous system (CNS) that is composed of rhabdoid cells, with or without fields resembling classical primitive neuroectodermal tumor. This tumor typically affects children younger than 3 years, and cases in individuals older than 18 years are rare, with an estimated lifetime risk of less than 1 in 1,000,000.2-4

Typically, a patient presents with an intracranial lesion. Approximately two-thirds of these tumors are located in the posterior fossa and one-fourth of them reside supratentorially; spinal involvement is very uncommon. The most suggestive radiographic feature of an ATRT is a posterior fossa mass, especially in the cerebellopontine angle, in a child younger than 2 years, showing intense enhancement, hyperdensity on CT scans, and hemorrhagic foci on T1-weighted MRI.5,6

The prognosis for patients with ATRT remains dismal, with historic median overall survival (OS) ranging from 6 to 18 months.1 In the 10 adult patients whose survival data have been reported in the literature, median survival was 15 to 18 months, although it ranged from 2 weeks to more than 17 years.7

Due to this tumor’s rarity and the lack of randomized controlled trials, it has been challenging to define optimal therapy and to make treatment advances. Radiation is an effective component of therapy, but it is avoided in patients younger than 3 years due to long-term neurocognitive sequelae. Most long-term survivors undergo radiation therapy as a part of their upfront or salvage therapy, and it has been suggested that sequencing the radiation earlier in therapy may improve outcomes. There is no standard curative chemotherapeutic regimen, but anecdotal reports advocate the use of intensive therapy with alkylating agents, high-dose methotrexate, or therapy that combines high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell transplant.8

Case Report

History and Examination

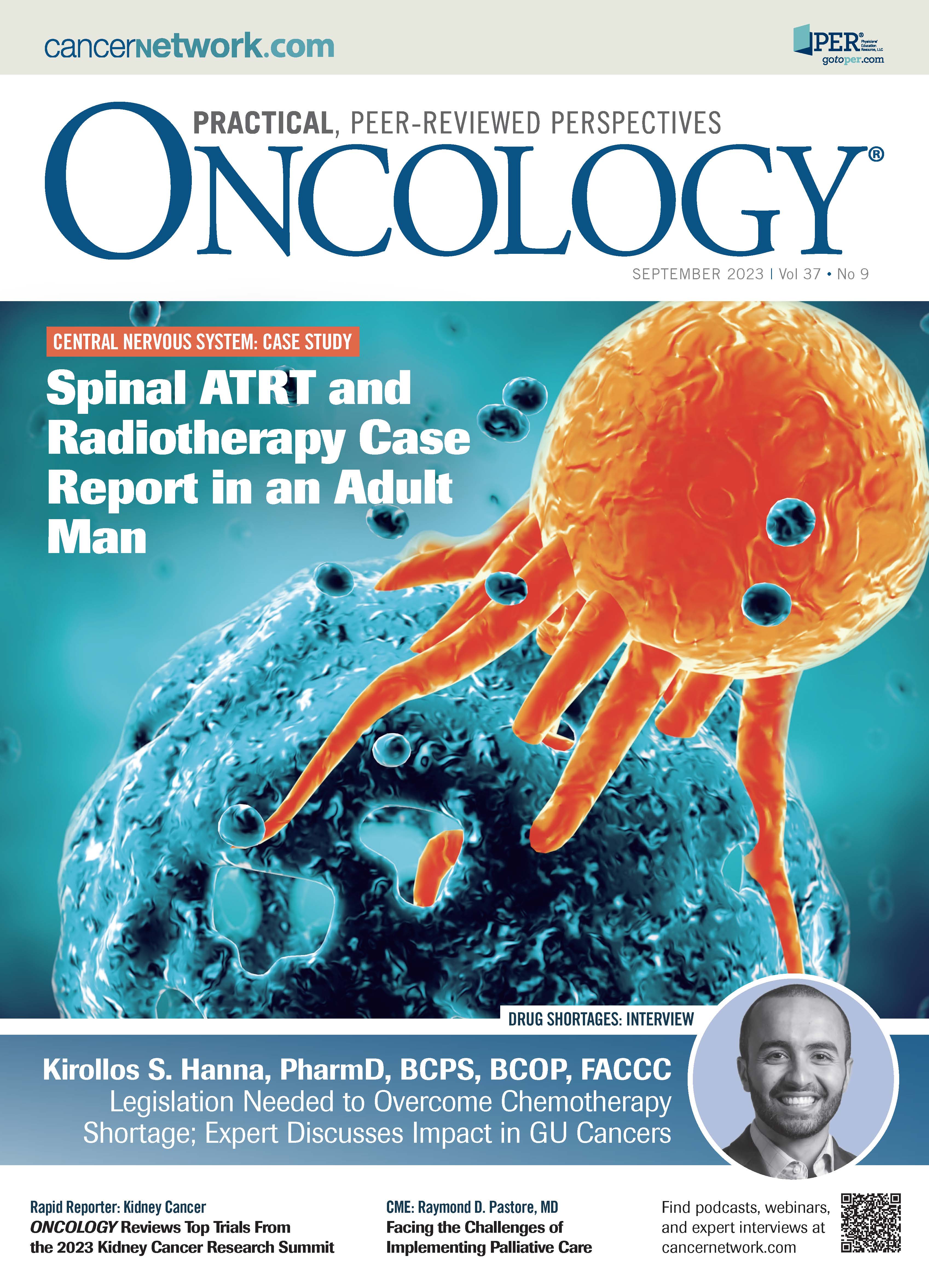

A male patient, aged 44 years, presented with neck pain and bilateral upper extremity paralysis. He had no previous known disease. In the preoperative MRI, a 25 x 17 x 19 mm intradural extramedullary mass extending from the cervicomedullary junction to the cervical (C) 2 to C3 vertebra level, causing compression on the left ventrolateral [side] of the spinal cord, was observed.

The lesion appeared isointense with gray matter on the T1 to T2 images. There was intense contrast enhancement in the lesion after the application of an intravenous contrast agent (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Preoperative MRI Cervical (Axial and Sagittal)

Initial Treatment: Surgery

The tumor was entered with a median suboccipital incision; C1 partial and C2 to C3 total laminectomy was performed. The intradural tumor was totally excised.

Pathological Findings

In serial sections of the material, on the background of thin-walled abundant vascular structures and thin muscle fibrotic bands, there was relatively narrow, vesicular, or slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm; it was interspersed with fine eosinophilic granular cytoplasmic inclusions, and it was coarse, round or oval, vesicular, pleomorphic, nucleolar prominent and irregular in contour. A hypercellular tumoral lesion consisting of atypical cells, some with nuclei showing frequent mitotic activity, was observed. In the immunohistochemical study, tumor cells were found to be diffuse positive with vimentin and CD99; diffuse negative (staining loss) with INI-1; PAN-CK focal positive; EMA rare weak positive; CD 138 focal weak positive; SALL-4 weak positive; and GFAP, CD34, ERG, S-100, HMB-45, SOX-10, SMA, desmin, CD117, and LCA were all negative. The tumor gave 40% to 45% positive reaction with Ki-67 in the most intense area.

Diagnosis: Atypical Teratoid Rhabdoid Tumor

Postoperative Process

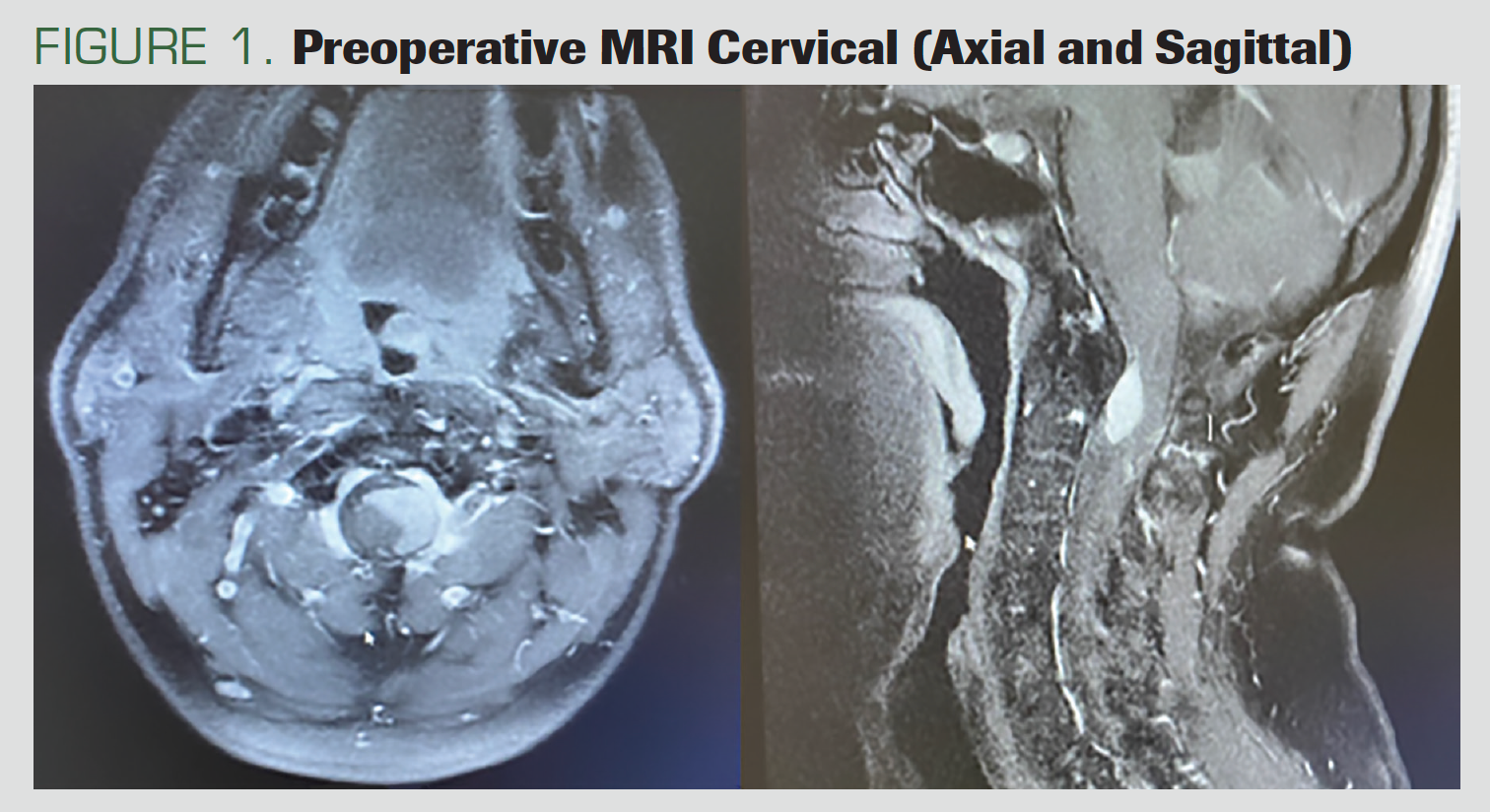

Six months after the surgery, the patient presented with quadriparesis that had developed within the previous week. He had stool and urinary incontinence as well as swallowing dysfunction. The MRI showed nodular mass lesions at the C2 level, located in the intradural extramural; they showed intense contrast enhancement, involving a segment of approximately 2 cm and reaching 0.8 cm at the widest part (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Postoperative MRI Cervical, Recurrence of Mass (Axial and Sagittal)

Surgery was not considered for the patient in his current state; instead, radiotherapy treatment was planned.

Radiotherapy

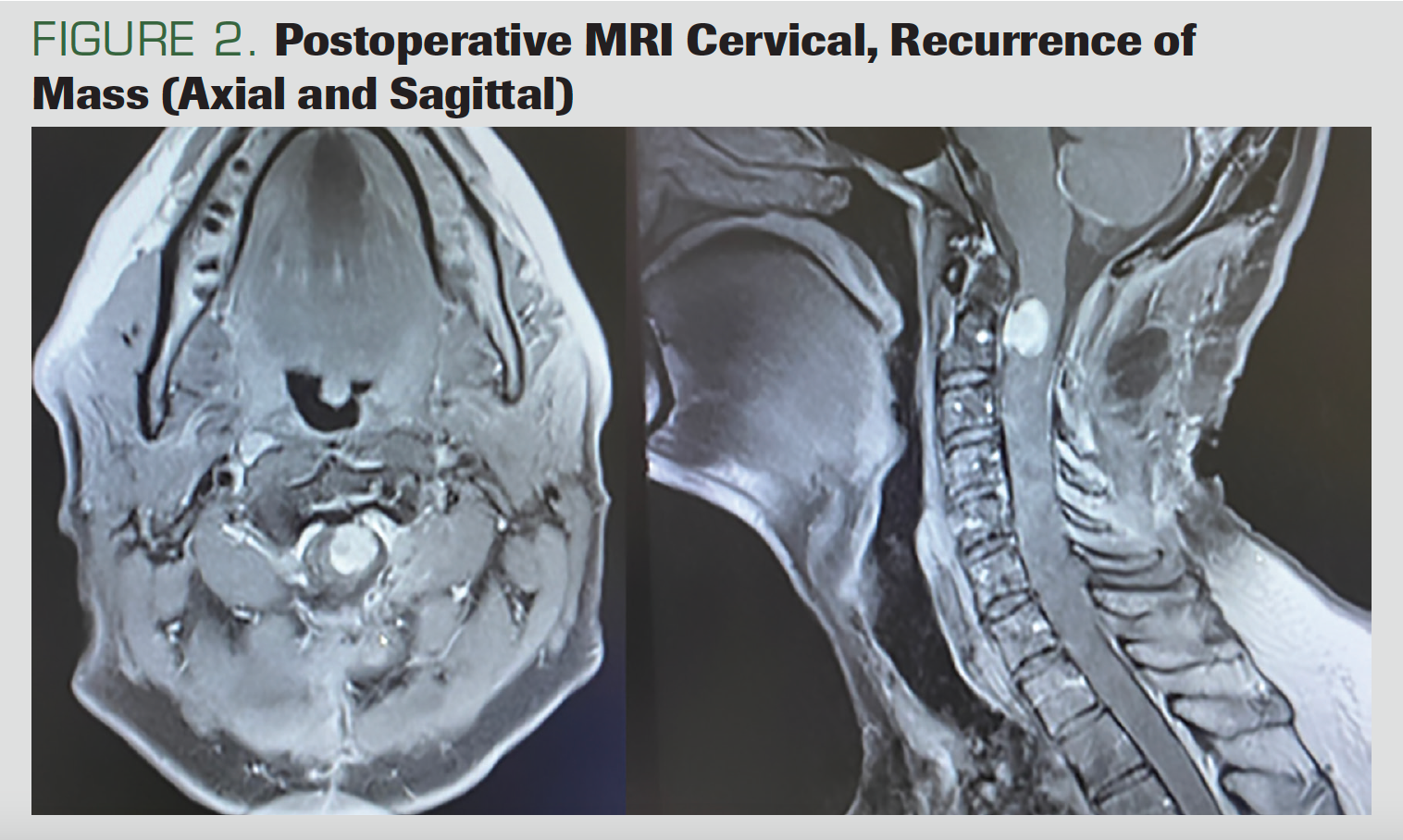

The CT simulation of the patient was performed in the supine position with a head-neck mask (Figure 3). We contoured the gross total volume (GTV) and all gross disease on the MRI. We created the clinical target volume (CTV) by giving a 1-cm margin to the GTV. We calculated the planning target volume by giving a 2-mm margin to CTV. Using the Hyperarc technique, we planned radiotherapy treatments totaling 4860 cGy: 180 cGy x 27 fractions. The medulla spinalis maximum dose was 49 Gy.

FIGURE 3. Radiotherapy Plan Images

Radiotherapy Process

The patient started to move his fingers and felt urine and stool after the fourth fraction. He started walking with a walker after the 14th fraction. When treatment was completed, upper and lower extremity motor strength was 4/5 bilaterally. Additionally, 4 x 4-mg steroid treatment had begun at the same time as radiotherapy started, but as the symptoms regressed, the dose was reduced by half and then, later, stopped altogether.

Postradiotherapy Process

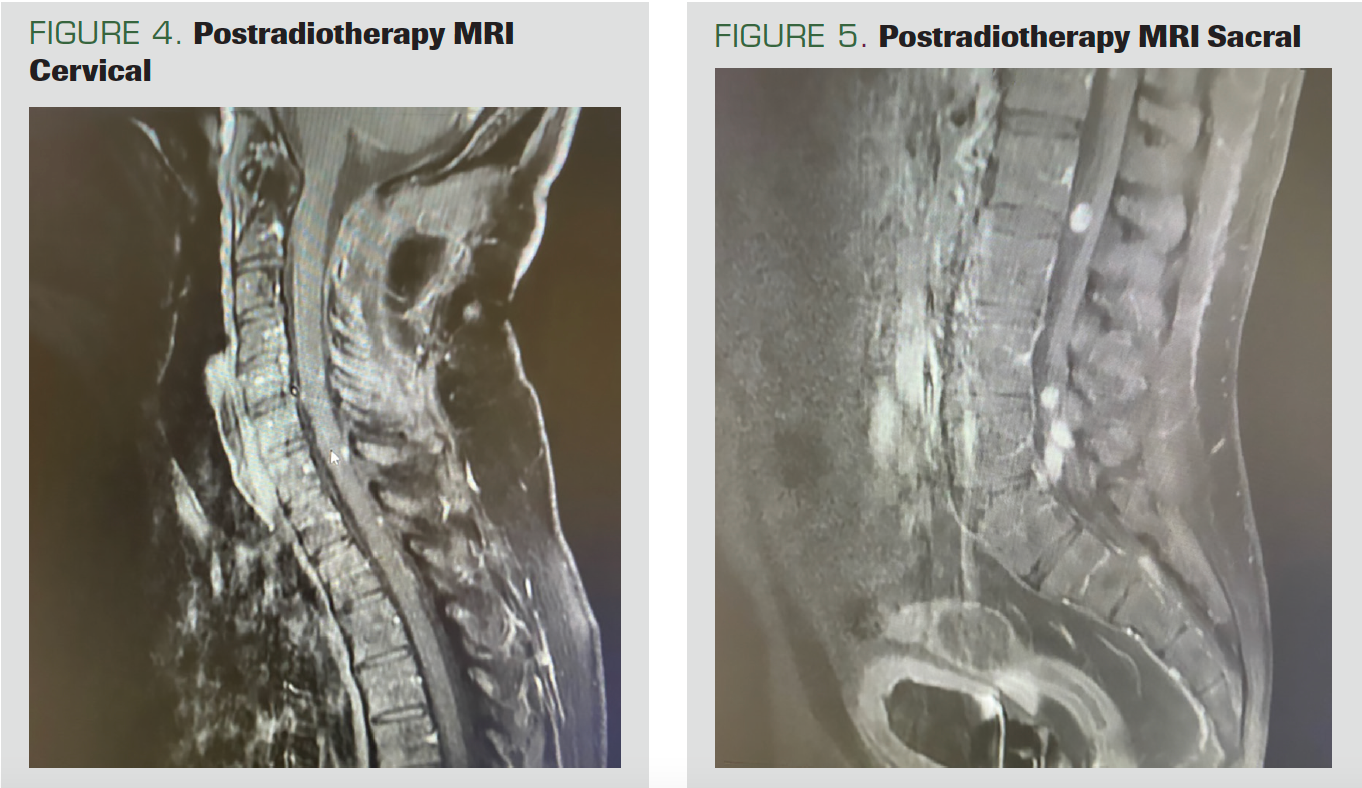

The patient, who came to the control after 2 months, had no adverse effects. No residual disease was found on the cervical MRI (Figure 4). However, nodular-shaped tumoral implants, all smaller than 1 cm, were noted on the spinal cord surface. Continuity of the implants was observed, starting from the distal thoracic spine segments on the thoracic, lumbar, and sacral MRIs and continuing up to the conus, suggesting the leptomeningeal spread of the existing tumor. In addition, leptomeningeal implants of neoplastic nature, the largest of which was approximately 1.1 cm in diameter, were observed within the fibers of the cauda equina in the distal conus medullaris (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4. Postradiotherapy MRI Cervical

FIGURE 5. Postradiotherapy MRI Sacral

The patient was started on a chemotherapy protocol of vincristine, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide. Craniospinal irradiation was also planned for the patient, because regression in the leptomeningeal involvement areas were seen in the MRI that was taken after 6 cycles of chemotherapy.

Craniospinal Irradiation

The CT simulation of the patient was performed in the supine position with a head-neck mask. The target volume was to the craniospinal area. Radiotherapy was planned at a dose of 36 Gy/20 fx with an intensity-modulated radiotherapy technique.

Post Craniospinal Irradiation

The patient, who came to the control 3 months after treatment, had no adverse effects. No pathological finding was seen on the craniospinal MRI.

Discussion

Spinal ATRTs in adults are more than just rare: Only 10 patients—including the present one—have been reported in the literature.6 Case reports and case series report an overall poor prognosis for such patients, with a median survival of 20 months. However, there are cases of adult patients with ATRT who have survived beyond 17 years from diagnosis. Preliminary results from the first prospective clinical trial in children with ATRT indicate that intensive multimodality treatment, including resection, CNS radiotherapy, and chemotherapy—based on the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group III protocol—may lead to longer survival, with an estimated mean (SD) 2-year OS rate of 70% (10%). Although the use of radiotherapy has been controversial, given the associated risk of adverse effects on the neurocognitive development of young children, emerging nonrandomized evidence indicates that radiotherapy may be important to achieve long-term survival in patients with ATRT.2,9,10

In a prospective study of 25 patients (median age, 26 months; range, 2.4 months to 19.5 years) by Chi et al, all received intensive multimodal treatment including surgery, induction chemotherapy, chemoradiotherapy, consolidation, and continuous chemotherapy. The study results indicated that this intensive multimodality treatment regimen led to improvement in OS and progression-free survival. However, the disease recurred in 8 patients between 2 weeks and 2.2 years after diagnosis.11

Because adult ATRT is so rare, a consistent treatment protocol has not yet been established. Currently, the management of ATRT in adults is based on data extrapolated from the pediatric literature. However, a multimodal approach that includes surgical resection, radiation, and chemotherapy has been taken in treating adult sellar region ATRT.2,10

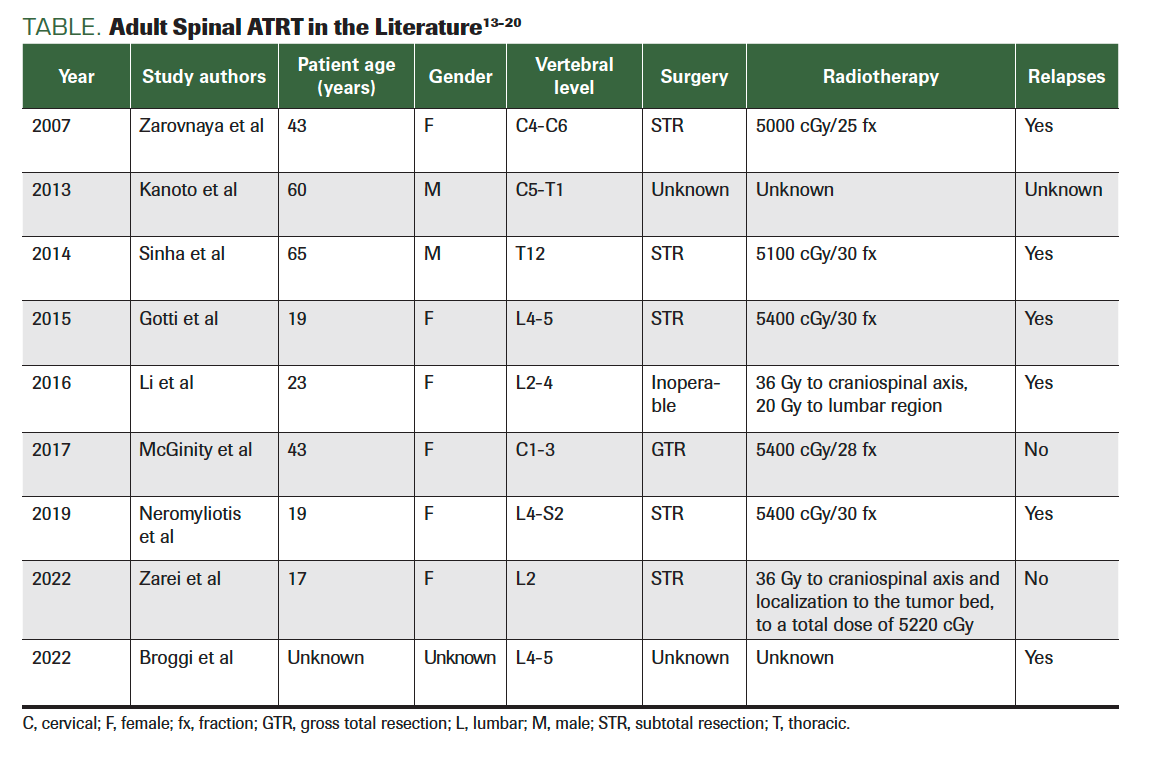

ATRTs are characterized by a loss of the long arm of chromosome 22, which in turn results in a loss of the hSNF5/INI-1 gene. The loss of INI1 expression is now regarded as a pathognomonic finding of an ATRT (Table).8,12

TABLE. Adult Spinal ATRT in the Literature13-20

Conclusions

In this case report, radiotherapy used in spinal ATRT treatment in an adult patient was shown to improve the patient’s symptoms.

More studies are needed for more accurate results.

Author Affiliations:

1Ankara Bilkent City Hospital, Radiation Oncology, Ankara, Turkey

2Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Radiation Oncology, Ankara, Turkey

Corresponding Author

Fatma Betül Ayrak

MD, Radiation Oncologist

Ankara Bilkent City Hospital, Radiation Oncology Clinic, Ankara, Turkey

Address: Ankara City Hospital, Radiation Oncology Clinic, Ankara, Turkey;

Universities quarter Bilkent Boulevard Ankara City Hospital Radiation Oncology Building, Çankaya, Ankara, Turkey

Tel: 905062410220

E-mail: fbetulgunes@gmail.com

The study has no sponsor.

References

- Chan KH, Mohammed Haspani MS, Tan YC, Kassim F. A case report of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumour in a 9-year-old girl. Malays J Med Sci. 2011;18(3):82-86.

- Chan V, Marro A, Findlay JM, Schmitt LM, Das S. A systematic review of atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor in adults. Front Oncol. 2018;8:567. doi:10.3389/fonc.2018.00567

- Tekautz TM, Fuller CE, Blaney S, et al. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors (ATRT): improved survival in children 3 years of age and older with radiation therapy and high-dose alkylator-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(7):1491-1499. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.05.187

- Woehrer A, Slavc I, Waldhoer T, et al; Austrian Brain Tumor Registry. Incidence of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors in children: a population-based study by the Austrian Brain Tumor Registry, 1996-2006. Cancer. 2010;116(24):5725-5732. doi:10.1002/cncr.25540

- Packer RJ, Biegel JA, Blaney S, et al. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor of the central nervous system: report on workshop. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24(5):337-342. doi:10.1097/00043426-200206000-00004

- Neromyliotis E, Kalyvas AV, Drosos E, et al. Spinal atypical rhabdoid teratoid tumor in an adult woman: case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2019;128:196-199. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.05.007

- Shonka NA, Armstrong TS, Prabhu SS, et al. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors in adults: a case report and treatment-focused review. J Clin Med Res. 2011;3(2):85-92. doi:10.4021/jocmr535w

- Ginn KF, Gajjar A. Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor: current therapy and future directions. Front Oncol. 2012;2:114. doi:10.3389/fonc.2012.00114

- Buscariollo DL, Park HS, Roberts KB, Yu JB. Survival outcomes in atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor for patients undergoing radiotherapy in a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results analysis. Cancer. 2012;118(17):4212-4219. doi:10.1002/cncr.27373

- Liu F, Fan S, Tang X, Fan S, Zhou L. Adult sellar region atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor: a retrospective study and literature review. Front Neurol. 2020;11:604612. doi:10.3389/fneur.2020.604612

- Chi SN, Zimmerman MA, Yao X, et al. Intensive multimodality treatment for children with newly diagnosed CNS atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(3):385-389. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7724

- Park HG, Yoon JH, Kim SH, et al. Adult-onset sellar and suprasellar atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor treated with a multimodal approach: a case report. Brain Tumor Res Treat. 2014;2(2):108-113. doi:10.14791/btrt.2014.2.2.108

- Zarovnaya EL, Pallatroni HF, Hug EB, et al. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor of the spine in an adult: case report and review of the literature.

J Neurooncol. 2007;84(1):49-55. doi:10.1007/s11060-007-9339-x - Kanoto M, Toyoguchi Y, Hosoya T, Kuchiki M, Sugai Y. Radiological image features of the atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor in adults: a systematic review. Clin Neuroradiol. 2015;25(1):55-60. doi:10.1007/s00062-013-0282-2

- Sinha P, Ahmad M, Varghese A, et al. Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumour of the spine: report of a case and literature review. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(suppl 4):S472-S484. doi:10.1007/s00586-014-3445-1

- Gotti G, Biassoni V, Schiavello E, et al. A case

of relapsing spinal atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT) responding to vinorelbine, cyclophosphamide, and celecoxib. Childs Nerv Syst. 2015;31(9):1621-1623. doi:10.1007/s00381-015-2755-x - Li L, Patel M, Nguyen HS, Doan N, Sharma A, Maiman D. Primary atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor of the spine in an adult patient. Surg Neurol Int. 2016;7:27. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.178523

- McGinity M, Siddiqui H, Singh G, Tio F, Shakir A. Primary atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor in the adult spine. Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:34. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.202132

- Zarei E, Anvari K, Arastouei S, Jafarian AH. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor in a young adult: a case report and literature review. Rep Radiother Oncol. 2021;8(1):e129043. doi:10.5812/rro-129043

- Broggi G, Gianno F, Shemy DT, et al. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor in adults: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis and additional reports of 4 cases. J Neurooncol. 2022;157(1):1-14. doi:10.1007/s11060-022-03959-z

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.

The Proper Ways to Identify and Use ADCs in Breast Cancer Subtypes

June 29th 2025Deciding when to use immunotherapy and how to utilize antibody-drug conjugates are complicated processes that require multidisciplinary collaboration to ensure that all patients with breast cancer receive appropriate and efficient care.