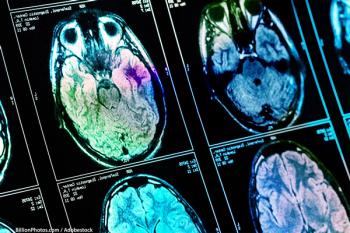

Genetics of Brain Metastases Reveal Potential Drug Targets

A genomic analysis of the primary tumors and brain metastases of patients has revealed potentially targetable mutations only present in the brain metastases.

An international team of researchers compared genomes from matching pairs of primary tumors and brain metastases, revealing potentially targetable gene mutations present in the brain metastases of patients that were not found in their primary tumors. The results were presented at the 2015 European Cancer Congress (ECC) in Vienna (abstract 2905) and simultaneously published in Cancer Discovery.

While the primary tumors and brain metastases had some overlapping genetic sequences, the analysis revealed that both samples evolved and diverged independently. The genomes of other metastatic sites and regional lymph node samples resembled one another but were very different from those of the brain metastases.

“The genetic divergence suggests that extracranial metastases may not serve as a proxy for clinical decision-making in patients with brain metastases,” Priscilla Brastianos, MD, director of the central nervous system metastasis program at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, told Cancer Network.

Dr. Brastianos also presented the data at ECC.

In 56% of the patients analyzed, the team found genetic alterations in the brain metastases-not found in the primary tumor-that could potentially be targeted with drugs.

“This study confirms the tremendous heterogeneity in metastatic cancer,” said Brastianos. “This divergent evolution has therapeutic implications, as brain metastases have clinically actionable genetic drivers that are not present in the biopsies of the primary tumors.”

The researchers performed whole exome sequencing on 104 matched primary tumors, brain metastases, and normal tissue to understand how the genomes of brain metastases evolve from initial primary tumors. For 20 of the patients, the team also had access to metastases in other parts of the body.

The sequencing analysis revealed that 52% of the mutations unique to brain metastases are potentially sensitive to cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors, while 43% of the alterations may be sensitive to PI3K or mTOR inhibitors.

About 8% to 10% of cancer patients go on to develop brain metastases, according to the authors. These tumors are typically quick to progress and there are few therapies-including radiation-that specifically target these central nervous system metastases. “Patients often progress in the brain with stable disease in other parts of the body. Historically, it is unclear if these differential responses are because of inadequate penetration of drugs into the brain vs genetic heterogeneity between the primary tumor and the brain metastases,” Brastianos explained. “Our study suggests that additional oncogenic drivers in the brain metastases may contribute to this clinical divergence.”

Brastianos and her colleagues will now explore whether specific drugs that target the brain metastases–specific mutations could lead to overall survival benefits for these cancer patients.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.