Oncology NEWS International

- Oncology NEWS International Vol 16 No 3

- Volume 16

- Issue 3

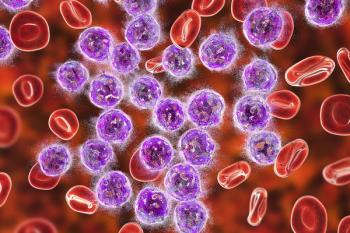

Imatinib Responses in CML May Take Time

While it may take more time than expected for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients to get a good response to imatinib (Gleevec), responses continue to improve with prolonged therapy

ORLANDOWhile it may take more time than expected for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients to get a good response to imatinib (Gleevec), responses continue to improve with prolonged therapy, according to a presentation at the 48th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology (abstract 2138).

Furthermore, a lack of a major molecular response (MMR) by 18 months should not necessarily trigger a change in therapy, said Michele Baccarani, MD, professor of hematology, University of Bologna, Italy.

The intent of the analysis was twofold: to determine whether cytogenetic and major molecular responses obtained at 12 or 18 months during imatinib therapy in the IRIS (International Randomized Study of Interferon vs ST1571) trial are predictive of 5-year outcome, and to see what proportion of patients who fail to achieve a cytogenetic response at those landmarks eventually achieve them with continued imatinib therapy.

Response Rates

Early results showed complete hematologic responses (CHRs) in all but 6% of patients by 3 months, and all but 4% by 6 months. Of this 4%, more than 80% achieved a major cytogenetic response (MCyR) by 18 months if they remained on therapy. Importantly, among patients with a complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) who had not achieved MMR at 12 months, about 70% later achieved MMR. In addition, among patients with CCyR but no MMR at 18 months, 50% ultimately achieved MMR.

Dr. Baccarani pointed out that since not all patients were subsequently followed with polymerase chain reaction (PCR), actual MMR rates would be presumed to be higher.

Of the 84 patients who had a partial cytogenetic response (PCyR) at the 12- month assessment, 64% achieved CCyR by 60 months. Of the 73 patients with no MCyR at 12 months, 36% ultimately achieved CCyR. Of 66 patients with PCyR and 56 with no MCyR at 18 months, 36% and 27%, respectively, achieved CCyR by 60 months.

Cytogenetic responses at the landmarks did correlate with outcomes (see Table). Estimated 60-month outcome analysis showed overall survival of 95% for those patients with CCyR at 12 months vs 90% and 80% for those with PCyR or no MCyR, respectively, at the same 12-month landmark. For those with CCyR, PCyR, or no MCyR at the 18- month landmark, the estimated 60-month overall survival rates were 97%, 90%, and 82%, respectively.

The same pattern persisted for event-free and progression-free survival. Event-free survival included progression to advanced disease, loss of MCyR or CHR, increase in white blood count, or non-CML death. Event-free survival was significantly higher for those with a CCyR at 18 months (98% with a ≥ 3 log reduction CCyR, 91% with a < 3 log reduction CCyR), compared to those with no CCyR (approximately 65%, P = .02). The impact of cytogenetic response at 18 months on 60-month progression-free survival was significant: 99% for CCyR, 90% for PCyR, and 83% for no MCyR (P < .001 for CCyR vs PCyR).

Overall, the impact of timing of response was not high. "Although clearly there is an advantage to an early response, the effect on long-term outcome is very small," Dr. Baccarani said. "The general message is that it may take more time than expected to get a good response with imatinib. If you don't have a CCyR at 12 months, the probable progression-free survival is still 93%."

Dr. Baccarani said also, "Since patients achieve MMR at different rates, a lack of MMR by 18 months may be too early for concern. It may suggest that a molecular response level alone should not trigger a change in therapy." Further study is needed to be able to identify which patients are likely to go on to become late responders or to respond to imatinib dose escalations.

Articles in this issue

almost 19 years ago

Peptide-Based Breast Ca Vaccines Promising in Early Trialsalmost 19 years ago

Diagnostic Dilemma: GI Diseasealmost 19 years ago

IV Vidaza Approved; Oral Formulation to Be Testedalmost 19 years ago

Study Confirms Avastin Advantage in Advanced NSCLCalmost 19 years ago

Legal Services Should Be a Component of Standard Cancer Carealmost 19 years ago

Mouse Virus Evidence Suggests Viral Basis for Breast Caalmost 19 years ago

Groups Oppose Ruling on Access to Experimental Drugsalmost 19 years ago

Satellite Allows Digital Mammography Screening for Rural Native Americansalmost 19 years ago

Nexavar Effective in Advanced HCC: Phase III Trial Stoppedalmost 19 years ago

H&N Ca Patients With CR to CRT May Not Need SurgeryNewsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.