- ONCOLOGY Vol 37, Issue 8

- Volume 37

- Issue 8

- Pages: 335-338

Unusual Initial Presentation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma as a Clavicular Head Mass

Rohit Gupta, MD, et al review a case study of a 70-year-old man who presented with a head mass, and the final diagnosis was hepatocellular carcinoma.

ABSTRACT

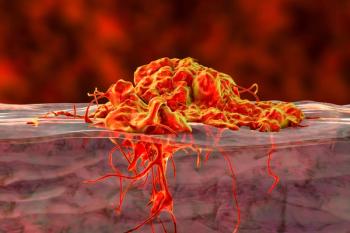

Background: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a common cancer worldwide. Extrahepatic spread is not unusual during HCC disease, but bone metastases at initial presentation are rare.

Case Description: We describe a case of HCC presenting with a clavicular head mass and spinal metastases with normal α-fetoprotein (AFP) level and hepatitis C virus infection without cirrhosis. After undergoing bone and liver biopsies, the patient started a 12-week course of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir and bevacizumab/atezolizumab for lifelong therapy with palliative intent. Since 2021, the patient has been receiving a combination of bevacizumab and atezolizumab every 21 days. On this regimen as of March 2023, his osseous metastases were stable and his liver lesions had not enlarged.

Conclusions: This case demonstrates a very unusual HCC presentation, the importance of a thorough workup of bone metastasis, and the limited value of AFP for HCC screening, even in disseminated disease.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is among the most common cancers worldwide, with incidence steadily increasing in the United States.1 The vast majority of HCC cases develop in the setting of liver cirrhosis and are diagnosed based on clinical evaluation, risk factor assessment, and imaging.1 Liver biopsy may be performed to confirm a diagnosis or evaluate suspicious lesions in atypical presentations.1 Prognosis of HCC is generally poor, with a median survival of 9 months from diagnosis.2 Extrahepatic spread frequently occurs, but it is present in only 5% to 15% of cases at diagnosis.2 Although the lungs are the most common site, metastasis also occurs to the bone—most frequently the vertebra—although this is rare at diagnosis and associated with significant morbidity and mortality.3 Here, we present a patient with a large clavicular head mass who was found to have HCC with spinal metastases in the setting of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection without clinical evidence of cirrhosis, an unusual presentation not previously described in literature.

Initial Presentation

A man, aged 70 years, with untreated HCV infection, alcohol use disorder, and tobacco dependence, presented with a 5 x 4 - cm left clavicular head mass of unknown duration (Figure 1). He also endorsed 6 months of decreasing appetite and weight loss. He denied any pain from the mass, cough, hemoptysis, hematochezia, melena, hematuria, urinary hesitancy, abdominal or back pain, nausea/vomiting, or skin changes. Organomegaly and palpable masses apart from the clavicular head mass were absent.

Diagnosis

A thoracic CT scan revealed a soft tissue clavicular mass and multiple lytic vertebral lesions (Figures 2A and 2B). A CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis identified 2 poorly defined hepatic masses. Liver mass protocol MRI showed an ill-defined area of enhancement within the periphery of the right hepatic lobe that demonstrated partial washout on the portal venous phase, and the liver surface was not suggestive of cirrhosis and did not have evidence of portal hypertension (Figure 2C). Admission laboratory studies showed that aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, serum albumin, prothrombin time, international normalized ratio, and platelets were within normal limits. HCV viral load was 10,400,000 IU/mL, and HIV and hepatitis B virus (HBV) core antibody/surface antigens were negative. α-fetoprotein (AFP), cancer antigen (CA)-19-9, CA-125, carcinoembryonic antigen, and prostate-specific antigen levels were within normal limits.

Assessment

To identify the primary site of the presumed metastatic disease, the clavicular mass was biopsied, and immunohistochemistry was strongly positive for arginase-1 and glypican-3 and negative for CDX2, CK7, CK20, and TTF-1. In conjunction with histology (Figure 3A), this was consistent with metastatic HCC. A liver mass biopsy confirmed the diagnosis, showing a similar lesion on histology (Figure 3B) and extensive sinusoidal vessel CD34 staining. Pathology review of the biopsy did not include surrounding

liver tissue.

Patient and Disease Management

The patient was started on a 12-week course of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir and bevacizumab/atezolizumab for likely lifelong therapy for palliation. Since 2021, he has been receiving a combination of bevacizumab/atezolizumab every 21 days. As of March 2023, his liver lesions and osseous metastasis had remained stable and had not enlarged. The patient did later develop a left upper lobe abscess of the lung, which was aspirated by interventional radiology. Microbiology revealed Proteus mirabilis, and the patient was treated for 21 days with levofloxacin with symptomatic improvement.

Discussion

We describe a patient diagnosed with HCC in the setting of chronic untreated HCV infection without clinical evidence of cirrhosis and with metastases to the axial and appendicular skeletons. Despite the burden of metastasis at presentation, the patient was largely asymptomatic with normal tumor markers, including AFP.

Bone involvement is rare at the time of HCC diagnosis, and few cases exist in the literature.4 The Table summarizes other patients from the literature with HCC who initially presented with bone involvement. In 395 patients with histopathologically verified HCC, patients with bone metastases at presentation (5%) were similar in clinical and demographic characteristics to those without; there was no significant difference in age, sex, AFP level, hepatitis B surface antigen seropositivity, or frequency of cirrhosis.4 When bone metastases occur with HCC, they are most often accompanied by musculoskeletal symptoms, frequently causing severe pain and deterioration in the quality of life.3 Metastatic spread to the bones has been described to occur in 13% to 16% of patients with HCC on average.3 The VEGF pathway has been implicated in bone metastases, with cells spreading via the hepatic portal system. The most common sites of skeletal involvement are the spinal column, pelvis, ribs, and skull.3,5 Multiple lytic bone lesions at the time of HCC diagnosis have been reported, but this is not as common as single-bone involvement.6 The prognostic significance of presenting with disseminated HCC has not been well explored, but studies suggest that developing bone metastases at any point during the disease course carries a poorer prognosis. Bhatia et al examined 1017 patients with confirmed HCC, 20 (2%) of whom developed bone metastases at some point during the disease course. These patients had a median survival following diagnosis of bone metastases of only 86 days (range, 16-2449).5 This is significantly shorter than the mean survival of HCC without metastases, which ranges from 6 to 20 months.7

Only 20% of HCC cases occur in a noncirrhotic liver.8 This subgroup generally presents with advanced-stage disease, as routine liver surveillance for HCC in the absence of cirrhosis is not currently recommended.1 Cases are often associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or chronic HBV. HCC in patients with noncirrhotic HCV represents only 4.4% to 10.6% of all HCC diagnoses.7 The risk of HCC in these patients increases with male sex, advanced age, diabetes, alcohol abuse, and coexisting hepatic steatosis.8 Although AFP levels may play a role in disease prognosis, a normal AFP should not be used to rule out HCC, as normal levels can be seen in all stages of the disease, from localized to widely metastatic, as observed in this patient.8 This is especially common in HCC without cirrhosis, where the sensitivity of AFP to detect disease is only 31% to 67%.8

The use of atezolizumab/bevacizumab in HCC has demonstrated markedly improved overall and progression-free survival for patients with advanced HCC, and treatment should begin as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed, including in cases with bone metastases.9 Patients with concurrent HCV infection should be treated for HCV following viral genotype testing, as some evidence suggests that treatment with antivirals may improve survival.10 However, concurrent HCV infection treatment should not delay HCC therapy initiation.

Our case demonstrates an atypical presentation of HCC with metastasis to skeletal and vertebral bone in a patient with chronic HCV uncomplicated by cirrhosis. We highlight the importance of a thorough workup to rule out usual bone metastasis causes. The case exemplifies how, because routine screening is not recommended in the absence of cirrhosis, HCC in a noncirrhotic liver generally presents with advanced-stage disease. The case also illustrates the limited value of AFP for HCC screening, even when the condition is widely metastatic. Despite an unusual presentation and multiple sites of metastasis at the time of diagnosis, our patient was still able to receive a timely diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatment under the coordination of a multidisciplinary care team.

Author Affiliations

1School of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA

2Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA

Author roles: RG and AT contributed to conception of the work idea. All authors contributed to drafting the work, revising the work, and the final approval of the version to be submitted.

Ethical Statement:All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 2013. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report as well as the accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review.

Funding: None

Article Guarantor & Corresponding Author:

Rohit Gupta, MD

Baylor College of Medicine

1 Baylor Plaza

Houston, TX 77030

Email: gupta.derm@gmail.com

Conflicts of Interest: No relevant conflicts of interest exist.

Grant Support/Funding: None.

Prior Presentation of Case: None.

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from the patient for case publication.

References

- McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2021;73 Suppl 1(Suppl_1):4-13. doi:10.1002/hep.31288

- Wang C-Y, Li S. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of 2887 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a single center 14 years experience from China. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(4):e14070. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000014070

- Ruiz-Morales JM, Dorantes-Heredia R, Chable-Montero F, Vazquez-Manjarrez S, Méndez-Sánchez N, Motola-Kuba D. Bone metastases as the initial presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. two case reports and a literature review. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13(6):838-842.

- Liaw CC, Ng KT, Chen TJ, Liaw YF. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting as bone metastasis. Cancer. 1989;64(8):1753-1757. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19891015)64:8<1753::aid-cncr2820640833>3.0.co;2-n

- Bhatia R, Ravulapati S, Befeler A, Dombrowski J, Gadani S, Poddar N. Hepatocellular carcinoma with bone metastases: incidence, prognostic significance, and management - single-center experience. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2017;48(4):321-325. doi:10.1007/s12029-017-9998-6. Published correction appears in J Gastrointest Cancer. 2017;48(4):390.

- Rastogi A, Bihari C, Jain D, Gupta NL, Sarin SK. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting with multiple bone and soft tissue metastases and atypical cytomorphological features - a rare case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41(7):640-643. doi:10.1002/dc.21838

- Golabi P, Fazel S, Otgonsuren M, Sayiner M, Locklear CT, Younossi ZM. Mortality assessment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma according to underlying disease and treatment modalities. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(9):e5904. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000005904

- Desai A, Sandhu S, Lai J-P, Singh Sandhu D. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-cirrhotic liver: a comprehensive review. World J Hepatol. 2019;11(1):1-18. doi:10.4254/wjh.v11.i1.1

- Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al; IMbrave150 Investigators. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894-1905. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1915745

- Cabibbo G, Celsa C, Cammà C, Craxì A. Should we cure hepatitis C virus in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma while treating cancer? Liver Int.2018;38(12):2108-2116. doi:10.1111/liv.13918

- Kim SU, Kim DY, Park JY, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting with bone metastasis: clinical characteristics and prognostic factors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134(12):1377-1384. doi:10.1007/s00432-008-0410-6

- Hwang SW, Lee JE, Lee JM, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma with cervical spine and pelvic bone metastases presenting as unknown primary neoplasm. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2015;66(1):50-54. doi:10.4166/kjg.2015.66.1.50

- Subasinghe D, Keppetiyagama CT, Sudasinghe H, Wadanamby S, Perera N, Sivaganesh S. Solitary scalp metastasis - a rare presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2015;9:4. doi:10.1186/s13022-015-0013-2

- Alauddin Z, Shahid A, Fatima N, Masood M, Qureshi A, Mirza ZR. Unusual presentation of bone metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma mimicking as breast lump. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2016(8);26:710-711.

- Monteserin L, Mesa A, Fernandez-Garcia MS, Gadanon-Garcia A, Rodriguez M, Varela M. Bone metastases as initial presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2017;9(29):1158-1165. doi:10.4254/wjh.v9.i29.1158

- Belli A, Gallo M, Piccirillo M, Iazzo F. Bone metastases as initial presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(9):e549. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30417-6

Articles in this issue

over 2 years ago

Avyakta Kallam, MD, on the Future of Mantle Cell Lymphomaover 2 years ago

Amivantamab vs Mobocertinib in Exon 20 NSCLCover 2 years ago

Current Treatments in Mantle Cell Lymphomaover 2 years ago

Drug Shortages: What Can Be Done to Alleviate Them?Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.