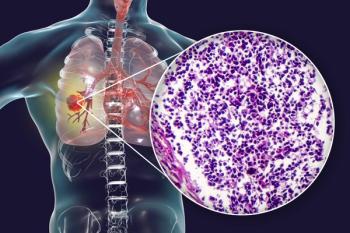

Confronting America’s Smoking Pandemic, Part 1: 1939–1966

Ahead of the World Tobacco Congress, Dr. Alan Blum and Cancer Network have partnered to assemble a four-part slideshow series addressing the history of America’s smoking pandemic. Part 1 examines the early evidence linking smoking with cancer.

Confronting America’s Smoking PandemicPart 1: From Early Evidence to Global Battle, 1939â1966Part 2: An Era of Activism, 1967â1985Part 3: Regulation, Legislation, Litigation, 1986â1999Part 4: Failures and Successes 2000â2016

References:

1. Ochsner A, DeBakey M.

2. Ochsner Health System.

3. Ventura HO.

4. Nelson J.

5. Justia US Supreme Court.

6. Wynder EL, Graham EA.

7. Levin ML, Goldstein H, Gerhardt PR, et al.

8. Doll R, Hill AB.

9. Ochsner A, DeCamp PT, DeBakey ME, Ray CJ.

10. Norr R.

11.

12. Hammond EC, Horn D.

13. Burney LE.

14. Welcome to the five-day plan to stop smoking: even to better living. General Conference of Seventh-Day Adventists. Washington, DC. 1962. p. 52.

15. McFarland JW, Folkenberg EJ. How to stop smoking in five days. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1964. p. 92.

16. McFarland JW, Gimbel HW, Donald WAJ, Folkenberg EJ.

17.

. London: Pitman Publishing Co. Ltd.; 1962.

18. Neuberger MB. Smoke screen: tobacco and the public welfare. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1963. p. 151.

19. US Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, Surgeon General’s Advisory Committee on Smoking and Health.

20. Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. Federal Trade Commission and Tobacco.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.