Bladder Cancer Management: Best Practices in Radiation Therapy

Focused discussion on the optimal use of radiation therapy strategies, alone or in combination with systemic therapy, for patients with advanced bladder cancer.

Episodes in this series

Transcript:

Petros Grivas, MD, PhD: Before I ask Lisa and Nerina [McDonald] a few more questions, Emily, let’s focus a little on radiation therapy. Let’s say we have a node-negative patient we’re discussing in our tumor board. What factors may help us direct the patient and help their decision-making between neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy followed by radical cystectomy and bladder preservation with trimodality therapy? [Are there] any nuances? [Are there any] patient- or tumor-related factors we discuss with the patient to help the decision point?

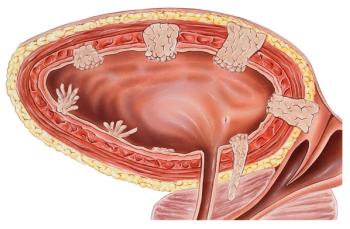

Emily S. Weg, MD: The optimal candidate for bladder preservation is someone who has unifocal disease, a tumor that’s not too big. Less than 5 cm would be ideal, with no extensive CIS [carcinoma in situ] and no hydronephrosis and a T stage of less than T3 or T3a. The patient has excellent baseline bladder function. The patient is a good candidate for cisplatin chemotherapy and is reliable for post-treatment surveillance. That’s the ideal candidate. Obviously, our patients don’t all look like that. But when we have 2 different treatment strategies and we’re trying to match the patient with the most appropriate approach, it’s good to keep in mind what the ideal candidate for bladder preservation looks like. Obviously, the ideal candidate for a radical cystectomy is a completely different list. But this is where, for a multidisciplinary conversation, it becomes helpful to be in the room discussing all the pros and cons, patient comorbidities, and specific clinical features of their disease. [Together we can] think about the best treatment strategy.

One thing we haven’t talked about yet but one of your favorite topics—I’m sure you’ll get there at some point—is variant histology. Looking at the pathology carefully with our bladder pathologist and thinking about how any component of variant histology might play into the picture is an important part of the discussion.

Petros Grivas, MD, PhD: These are all such important points, Emily. Thank you for outlining them. Variant histology is definitely a priority for our program in terms of research. We have a couple of new adjuvant clinical trials in patients who go for cystectomy looking at variant histology, and Nerina and I have set up many of those patients. To your point, all those factors are taken into account, and this shows the value of the multidisciplinary tumor board we have every Tuesday morning at [the] University of Washington: to go through those factors with the patients and help tailor our recommendation during the individual scenario as much as we can. Nothing is perfect. Usually, some particular factors may point to 1 direction or another, and of course [we have] patient preferences. It’s great to have these options. There’s definitely an opportunity to use bladder preservation in our patients, and we’re doing a better job presenting the option to the patient. We should in appropriate patients, and it’s great to have you and others in [the] radiation oncology field contributing so much. Can you comment briefly on the duration of radiation, 4 weeks and 6 weeks? [Are there] any nuances there?

Emily S. Weg, MD: Planning radiation for bladder cancer is a little like choosing your own adventure. There are so many ways to do it. There are a lot of decision points for the radiation oncologist. The first question is, do you want to use conventional fractionation, which is 6 to 7 weeks, or a moderate hypofractionation, which is 4 weeks of treatment? Another decision point is whether you’re going to treat the bladder only or the bladder with the pelvic lymph nodes. Another decision point is whether you’ll boost the bladder. If you do, are you going to boost the whole bladder or partial bladder? [There are] a lot of different decision points.

Over the last few years, the field has been moving toward moderate hypofractionation. When I speak with colleagues from across the country around, 55 Gy in 20 fractions, 4 weeks of treatment is becoming a much more common approach. It’s more straightforward. The longer conventionally fractionated treatment was the treatment that at midpoint, or the halfway point of 25 treatments. You’d pause, go into the urologist, have another cystoscopy, and assess for treatment response. That’s fallen out of favor. That’s not common practice anymore.

If you look at some of the trials that we have open around the country, the ones we’ve mentioned already—SWOG S1806, ECOG-ACRIN—use conventional fractionation. In my practice, I treat 55 Gy in 20 fractions, or 4 weeks of treatment, for most patients, unless they’re on trial where we have to use conventional fractionation or they’re node-positive. If they’re node-positive and we’re going to be treating the lymph nodes, then they’re getting conventionally fractionated treatment in 6 to 7 weeks.

Petros Grivas, MD, PhD: Thank you, Emily. [This is a] great discussion. It obviously depends on the duration of treatment. You don’t have to a shorter duration in node-negative disease. It’s convenient for patients who live far away. Of course, you customize based on individual characteristics. With more bulk tumors and concern for node-positive disease, you may go for conventional fractionation. For most of these patients, we try to give them concurrent chemotherapy as a radiation-sensitizing agent. We have 3 options: cisplatin weekly, 5-FU [5-fluorouracil] and mitomycin C based on the data from the United Kingdom, or gemcitabine. Our practice has been to give cisplatin to fit patients, and we tend to give gemcitabine-cisplatin to fit patients for simplicity and convenience.One thought that comes to mind is that in cisplatin-fit patients, gemcitabine has been well tolerated. We have senior patients who, when we try to get them through, especially with 4 weeks of radiation—just 4 weekly doses—seem to be doing pretty well. Lisa, any comments on that for desensitizing chemotherapy?

Lisa Adams, PA-C: If someone wasn’t a cisplatin candidate, our preference also would be gemcitabine for tolerance. I have a few in mitomycin C. Sometimes it can be a bit tough with mucositis and diarrhea. We like gemcitabine in cisplatin-ineligible patients.

Petros Grivas, MD, PhD: Our practice aligns. I had this discussion with our friends in the United Kingdom. They had the phase 3 trial, so it’s an important point, with 5-FU [5-fluorouracil] and mitomycin Nicholas James and colleagues did that trial, the BC2001 trial. We have phase 2 trial data with gemcitabine. Technically it’s a high level of evidence with 5-FU [5-fluorouracil] and mitomycin C, but with the complexity, the pump, the logistics, the adverse effect profile, and toxicity, we tend to gemcitabine for simplicity and patient convenience, in cisplatin-fit patients at least.

Transcript edited for clarity.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.