Building Efficiency and Scaling With a Remote Genetic Counseling Program

Smita K. Rao, MBBS, MS, et al gave an overview of implementing genetic counseling into oncology practices through telemedicine.

ABSTRACT

Purpose

A third-party telemedicine (TM) genetic counseling program was initiated at a large community oncology practice spanning 35 clinical sites with

110 clinicians and 97 advanced practice providers throughout Tennessee and Georgia.

Patients and Methods

Appropriate patients were referred through the electronic health record (EHR) based on current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. A combination of TM and genetic counseling assistants enhanced convenience, broadened access, and decreased no-show rates. Physician education for mutation-positive screening recommendations was provided through deep integration of dedicated genetic counseling notes in the EHR.

Results

From 2019 to 2022, the program expanded from 1 to 20 clinics with referrals growing from 195 to 885. An average of 82% of patients completed genetic counseling consultations over TM with more than 70% completing genetic testing. The average was 4 to 6 days from referral to consultation. The no-show rate was maintained at less than 7%. In 2023, this model supported all 35 clinics across the state.

Conclusion

Our program illustrates how remote genetic counseling programs are an effective choice for scaling genetics care across a large community oncology practice. Deep integration of TM genetic counseling within the EHR helps identify patients who are high risk and improves test adoption, patient keep rate, and turnaround time, helping to achieve better patient outcomes.

Background

Genetic counseling started as a specialty service in prenatal and pediatric patient populations in the 1970s and expanded to cancer care in the 1990s. Initially, it was used only to identify hereditary cancer syndromes in affected patients and define the risk for unaffected family members. Now the utility of genetic testing and therefore the scope for cancer genetic counseling have expanded to determining treatment options through surgical interventions and genetic profiling to direct appropriate chemotherapy options. These advancements have forced genetic counseling to become integral in comprehensive cancer care, with genetic testing offered earlier in the diagnostic process to facilitate clinical decision-making.1

Through this evolution, the field of cancer genetic counseling faced multiple challenges. First there was a supply-side workforce shortage. Prior studies have reported approximately 1 genetic counselor (GC) for every 300,000 Americans and equated it to 8 GCs for 1 million individuals in the United States population.2,3 In 2017, the Genetic Counselor Workforce Working Group, conferred under the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC), projected that the demand for the genetic workforce to have 1 GC for every 100,000 Americans would be met in 2023 to 2024, which is said to have been attained.4 Further increase in demand to 1 GC for every 75,000 Americans might not be met until 2029 to 2030, but given the recent growth in genetic counseling training programs it could be anticipated by 2026.5

The second challenge was in the ever-expanding National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines testing criteria. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic per source6 and NCCN Guidelines for Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal7 provide evolving clinical guidance to identify patients who should be offered a hereditary genetic panel test. To determine how much in demand GCs were, an independent objective assessment by a study from Greenberg et al found that 21.6% of patients with cancer met NCCN guidelines at the time of the study in 2019, and that proportion increased to 62.9% when family history was taken into account.8 Other publications that same year reported that even though NCCN guidelines were considered one of the standard tools to help identify individuals eligible for germline genetic testing, these criteria continue to fail to identify women with breast cancer who carry BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations.9,10 Since then, NCCN guidelines have continued to be more inclusive for patients affected by cancer and those who do need germline genetic testing. A study done by Yadav et al in 2020 found that the NCCN criteria had an 87% sensitivity rate and 53% specificity rate to help identify BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers among 3907 women with breast cancer. They suggest that further expanding the NCCN criteria to test all women 65 years and older at breast cancer diagnosis would improve the sensitivity such that women carrying pathogenic mutations would not be missed.11

The third challenge was in the traditionally entrenched service delivery model. Innovation was a key need as multiple studies cited long wait times and lack of access to genetic counseling.12,13 The customary 1-hour pretest appointments gave way to alternate models: some GC directed, such as group counseling or TM counseling, and some non–GC directed, where education and informed consent are provided by prerecorded video, web-based education, chatbots, or interactive relation agents.1

Although TM (audiovisual or audio only) has been used for genetic counseling for over a decade, its implementation has increased drastically since 2019 for various reasons. According to a Professional Status Survey (PSS) on access and service delivery by the NSGC, the completion of counseling visits over the phone rose from 36% in 2019 to 74% in 2021. Similarly, 28% of GCs reported using audiovisual TM in 2019 compared with 82% in 2021.14 Studies have shown that these alternate service delivery models increase patient convenience by mitigating travel and wait time–related barriers, improve patient satisfaction, and are ultimately successful in meeting the growing demand for genetics services.15

The advent of genetic counseling assistants (GCAs) also helps meet the growing demand for services. Previous literature shows that certified GCs with GCA support can see an average increase of 60% in patient volume compared with GCs alone, thereby expanding access to the genetic counseling services.16 Another study demonstrated that GCAs assist GCs in focusing on the direct patient care for which they are specifically trained by significantly reducing the time taken to prepare for a patient appointment, and significantly increase the total number of patients seen per week (7.9 vs 11.4 after using GCA support).17

Here, we report on an efficient service delivery model for GC that incorporates a third-party TM-based genetic services vendor with deep integration into the electronic health records (EHRs) to scale the implementation of genetic counseling services in a community-based oncology setting across 35 clinics. The significance of this model is in the efficiency built into the patient engagement where GC consults do not add time to the genetic testing process.

Methods

A TM genetic counseling program using a third-party genetics vendor was initiated in 2019 at Tennessee Oncology (TO), a large community oncology practice spanning 35 hematology/oncology clinical sites with 110 doctors and 97 advanced practice providers (APPs) throughout Tennessee and North Georgia. TO’s core expertise is in onsite chemotherapy treatments, so patients may receive the necessary care without the strain of long-distance travel. TO, one of the nation’s largest, community-based cancer care specialists, is home to one of the leading clinical trial networks in the country. Over the years it has been consistent with its mission statement to provide high-quality cancer care and the expertise of clinical research for all patients at convenient locations within their community and close to their home.18 Therefore, incorporating a TM-based genetic counseling and testing program fits well with TO’s mission and long-term vision.

In initiating the first genetics program at this practice, a total of 3 to 4 months was spent in discovery, infrastructure development, and establishing process flow to support the genetics team. In the discovery phase, an in-depth study of patient intake documents for new patient charts and existing lab processes was undertaken. Members of the genetics team shadowed physicians and advanced practice nurses to understand the clinic flow in terms of clinic appointments, lab orders, and front desk scheduling activities. During the infrastructure development phase, family history elements were added to the new patient intake paperwork, and specific lab orders were built for germline genetic tests. Custom genetics fields were set up within the EHR for exclusive use by the genetics team for consultation notes and clinic templates for scheduling. In the third and final phase of establishing a process that could be duplicated at every clinic site, a project management workflow was created in partnership with the operations team at TO. Front office, clinical, and billing workflows were created. Incorporating genetic services at various clinics began with the training of lab and front desk staff on the new service line, simultaneously with educational touch points for physicians and APPs on current NCCN guidelines. Decision aids were also built into the EHR to help appropriately capture patients who might meet these guidelines, but they were quickly abandoned due to technical challenges. All referrals were entered through the EHR to promote tracking for genetic counseling and testing.

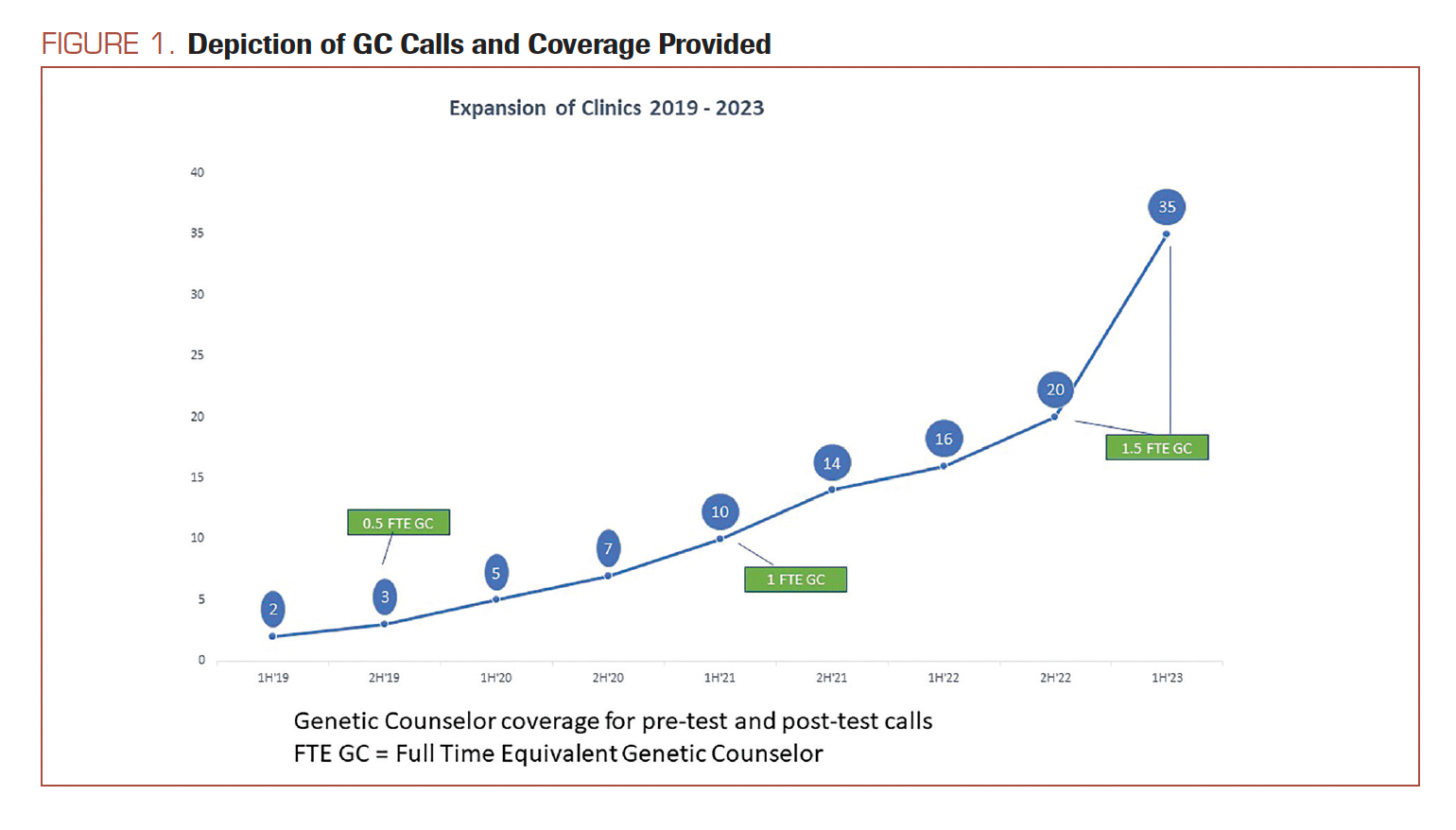

GCAs were assigned to support front office staff at TO for scheduling all GC consults over TM. Protocols were created to triage scheduling for urgent referrals within 1 to 3 business days, and nonurgent referrals to not exceed 4 to 6 business days of wait time for patients. Particular attention was allocated to patients with pancreatic cancer, metastatic prostate cancer, or metastatic breast cancer diagnoses to assess eligibility for PARP inhibitor chemotherapy. Other urgent appointments were categorized as newly diagnosed patients with breast cancer undergoing surgical planning and patients carrying Cigna insurances with a requirement for genetic counseling services to precede the genetic test orders.19 Referrals meeting these urgent criteria were invited from all 35 clinic sites practice-wide right from the onset. For nonurgent referral types (defined as patients affected by cancer meeting other NCCN criteria), the program was introduced 1 clinic site at a time as detailed in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Depiction of GC Calls and Coverage Provided

All GC appointments were scheduled as TM audio and visual visits, which were switched to audio only (phone) if requested by the patient. TM calls were held either over Zoom or Doxy.me to the patient’s home or workplace, usually outside clinic hours, and therefore considered asynchronous to their in-person oncologist’s appointment. Additionally, genetic counseling sessions and notes were completed independently of the oncologist.

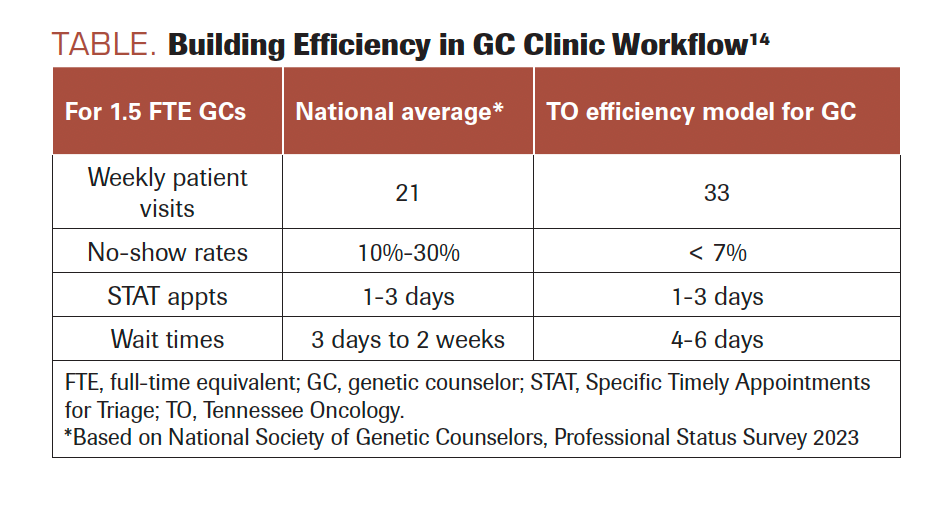

By the end of 2022, the GC team at TO had 1.5 full-time equivalent (FTE) of genetic counselor time and 1 FTE of GCA time. As there was not an established genetics service at TO prior to initiating this program, the performance metrics of this new service delivery model for GC are compared against the national averages for genetic counseling services published in 2023 by NSGC in its PSS document.11

Results

In the first year, the service was piloted at 1 TO clinic site for 3 months,

(January-March 2019) with 5 clinicians and 4 APPs using all the functionality of the program. Prepilot data from 2018 showed a total of 7 patients consented to genetic testing at that particular initial clinical site. During the pilot phase, 34 patients were referred for genetic counseling and 30 completed genetic tests. This result demonstrated a 5-fold increase in identifying and appropriately testing patients and was published as an abstract at the 2019 American Society

of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting.20

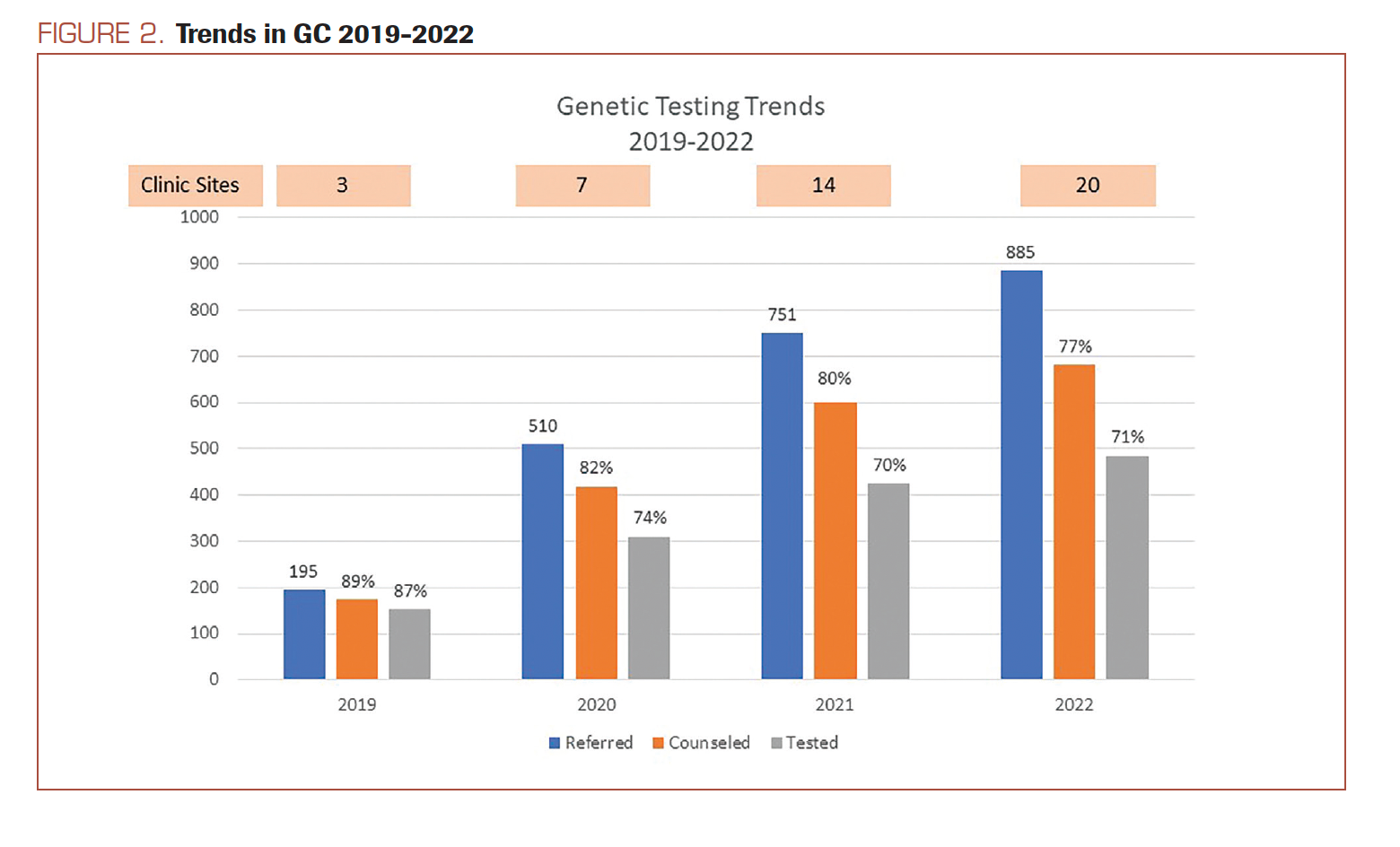

Based on the success of the pilot, the TM-based genetic counseling service progressively rolled out to more clinics across the state of Tennessee. Starting with 3 clinics in the first year, the incorporation of clinical sites into the program progressed to 7 sites at the end of 2020, 14 sites at the end of 2021, and 20 sites at the end of 2022. In 2023, with the beginning of year 5, the program had expanded to all 35 clinics across the practice (Figure 1).

Breakdown of the referral volume indicates the largest growth in referral numbers for genetics in year 2 by 160%. Although tapered now to a 20% year-over-year increase for 2022, the cumulative growth for genetic counseling referrals over the past 4 years (2019-2022) was 350% (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Trends in GC 2019-2022

As shown in Figure 2, consistently over 77% of patients completed genetic counseling consultations over the years, with a high of 89% in 2019. Of the completed consultations, over 70% of patients completed genetic testing with a high of 87% seen in 2019 (Figure 2). The no-show rate is consistently less than 7% for the program (Table 1).

TABLE. Building Efficiency in GC Clinic Workflow14

Comparing results against national averages, for a staff of 1.5 FTE GCs and 1 GCA, this efficient service delivery model for genetic counseling offers a higher number of available slots per week for counseling appointments (33 vs 21), a lower no-show rate (< 7% vs 10%-30%), and comparable wait times for urgent (1-3 days) and nonurgent (4-6 business days) referrals (Table 1).

Discussion

A third-party genetics team of TM-based GCs was brought on in 2019 to facilitate appropriate genetic test ordering and offer comprehensive cancer care for patients at TO. In the genetic counseling profession, amid discussions about a dearth of genetics professionals, we describe a fully scaled genetic counseling and testing program offered over TM with deep integration of the EHR at 35 clinical sites in a community-based setting.

The efficient service delivery model for GCs deployed at TO facilitates a clinic workflow wherein the third-party GCs and GCAs are in direct EHR-based communication with the oncologist and their clinical team, which, in turn, promotes higher adoption of the service. The effectiveness of this model is seen in higher patient engagement with genetic counseling services due to the convenience of TM conducted asynchronously to the oncologist’s in-person appointment.

After initially proving the success of the pilot program,20 the next challenge was to scale this service across all clinical sites. With this efficient service delivery for the genetic counseling model, the scalability of genetic counseling services persisted through years 2, 3, and 4 as the program was rolled out at more than half of the existing clinics over TM by the end of 2022 (Figure 1). Currently, in year 5, the TM-based GC team supports all 35 clinics with no increased wait times or no-show rates. This scalability is powered by the effective use of TM in combination with the deep integration of GC’s and GCA’s into the hospital EHR as a service modality.

TM genetic counseling appointments at the patient’s home or workplace enhance access, decrease no-show rates, and promote patient engagement. Built on the proven efficacy of TM,15 this genetics service was established as a remote program before the COVID-19 pandemic years. Expansion of services showed consistent growth through 2022. The consistency of completed genetic counseling appointments and genetic test uptake by patients demonstrates the seamless use of this service modality for scaling genetic counseling (Figure 2). Although not measured yet, based on anecdotal patient engagement, patient satisfaction with the TM service is not hindered. This quality improvement enhancement is planned for the next phase of maintaining the relevance of the service.

Performance metrics for the program, described above, indicate that this integrated genetic counseling program is more efficient in available consult slots than national averages for GCs. The program maintained a 4 to 6 business-day wait time even with a significant uptick in the referrals in year 2 when a decision support aid was in use in the EHR to help physicians talk about genetics with their patients and update family history information during the clinic visit. This aid was disabled at the end of year 2 and deferred for future use after completing program integration across all 35 clinical sites. We plan to make further attempts at building a decision support tool in the EHR in 2023.

Per standard recommendations in the field, incorporating 1 GCA of FTE support has been key in improving the efficiency of our GC team.13 The GCAs schedule TM patient appointments for genetic counseling for each TO clinical site. They function as the point of contact in the clinic and liaise with lab personnel and operations managers to help coordinate dispatching and tracking tests and uploading genetic reports. GCAs also assist in care coordination by being the conduit with the genetic testing labs, overseeing specimen processing and timely retrieval of reports. The overall impact of a GCA is greater than the sum of their role. They are the first to educate patients on the need for genetic counseling. They also shepherd clinic personnel on how to navigate the genetic testing process.

The appropriate implementation of a combination of TM with the use of GCAs coupled with EHR integration helps alleviate the administrative and operational burden of adding genetic services to an already busy

community-based oncology service. With the addition of GCAs, GCs work at the top of their license to interpret results, conduct variant assessments, and dictate medical care plans for patients who are mutation positive per the current standard-of-care guidelines in the industry. This model proves the management of clinical efficiency and scalability for genetic counseling to be on the front line in multiple clinics. The genetic counseling consults are completed within 4 to 6 business days and do not delay the genetic testing. Rapid turnaround times support quality medical care as complete and verified genetic results are made available to providers promptly in the EHR.

The ultimate success of the program is in the deep integration of this remote service into the EHR. All notes and pedigrees are uploaded as unique fields in the EHR and not as scanned documents. Communications with clinic staff and physicians are conducted through an EHR messaging system and completed notes in the patient charts to extend transparency into the workings of the remote team.

Initiatives for this program in the coming year include electronic decision support tools, additional provider education, and the development of management algorithms for patients who are mutation positive. We also plan to incorporate patient engagement tools to further expedite the process and deploy patient satisfaction surveys to offer superior patient care. For a large, community-based oncology center that is focused on high-quality comprehensive cancer care for all its patients, this efficient service delivery model for genetic counseling scales to fit all its clinical site needs and has bandwidth to incorporate additional referrals and clinics as it expands. We encourage genetic counseling programs to incorporate the described service delivery model to build efficiency and promote quality genetics care for patients.

Conclusion

As germline genetic testing integrates further into oncology care, GCs will increasingly partner with community-based cancer centers. Our program illustrates how remote genetic counseling programs can build efficiency and are an effective choice for scaling genetics care. Building efficient teams includes collaborating with the clinic site to integrate workflow without disruption. Deep integration of TM-based genetic counseling within the EHR helps identify patients who are high risk and improves test adoption, patient keep rate, and turnaround time, therefore helping to achieve better patient outcomes. Maintaining an open channel of communication with the clinic staff and oncologists through an EHR-based messaging system helps build transparency and trust. This efficient service delivery model for genetic counseling and testing programs is an important, successful part of comprehensive cancer care.

Corresponding Author

Smita K. Rao, MBBS, MS,

422 Harding Road #200

Nashville, TN, 37205

Phone: 615-385-3751

Fax: 615-269-7085

Email: smita@genexsure.com

References

- Schienda J, Stopfer J. Cancer genetic counseling-current practice and future challenges. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2020;10(6):a036541. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a036541

- Pal T, Radford C, Vadaparampil S, Prince A. Practical considerations in the delivery of genetic counseling and testing services for inherited cancer predisposition. Community Oncol. 2013;10(5):147-153. doi:10.12788/j.cmonc.0010

- Radford C, Prince A, Lewis K, Pal T. Factors which impact the delivery of genetic risk assessment services focused on inherited cancer genomics: expanding the role and reach of certified genetics professionals. J Genet Couns. 2014;23(4):522-530. doi:10.1007/s10897-013-9668-1

- Genetic counselor workforce. National Society of Genetic Counselors. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://shorturl.at/pzM39

- Hoskovec JM, Bennett RL, Carey ME, et al. Projecting the supply and demand for certified genetic counselors: a workforce study. J Genet Couns. 2018;27(1):16-20. doi:10.1007/s10897-017-0158-8

- NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian and pancreatic, version .2.2024. Accessed December 8, 2023. https://bit.ly/3t58A8t

- NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, version.1. 2022. Accessed December 8 2023. https://bit.ly/2EVRHlm

- Greenberg S, Buys SS, Edwards SL, et al. Population prevalence of individuals meeting criteria for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer testing. Cancer Med. 2019;8(15):6789-6798. doi:10.1002/cam4.2534

- Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Hughes K, et al. Underdiagnosis of hereditary breast cancer: are genetic testing guidelines a tool or an obstacle? J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(6):453-460. doi:10.1200/JCO.18.01631

- Yang S, Axilbund JE, O’Leary E, et al. Underdiagnosis of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in Medicare patients: genetic testing criteria miss the mark. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(10):2925-2931. doi:10.1245/s10434-018-6621-4

- Yadav S, Hu C, Hart SN, et al. Evaluation of germline genetic testing criteria in a hospital-based series of women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(13):1409-1418. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.02190

- Khan A, Cohen S, Weir C, Greenberg S. Implementing innovative service delivery models in genetic counseling: a qualitative analysis of facilitators and barriers. J Genet Couns. 2021;30(1):319-328. doi:10.1002/jgc4.1325

- Cohen SA, Huziak RC, Gustafson S, Grubs RE. Analysis of advantages, limitations, and barriers of genetic counseling service delivery models. J Genet Couns. 2016;25(5):1010-1018. doi:10.1007/s10897-016-9932-2

- Professional status survey. National Society of Genetic Counselors. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://shorturl.at/adrvC

- Buchanan AH, Datta SK, Skinner CS, et al. Randomized trial of telegenetics vs. in-person cancer genetic counseling: cost, patient satisfaction and attendance. J Genet Couns. 2015;24(6):961-970. doi:10.1007/s10897-015-9836-6

- Pirzadeh-Miller S, Robinson LS, Read P, Ross TS. Genetic counseling assistants: an integral piece of the evolving genetic counseling service delivery model. J Genet Couns. 2017;26(4):716-727. doi:10.1007/s10897-016-0039-6

- Hallquist MLG, Tricou EP, Hallquist MN, et al. Positive impact of genetic counseling assistants on genetic counseling efficiency, patient volume, and cost in a cancer genetics clinic. Genet Med. 2020;22(8):1348-1354. doi:10.1038/s41436-020-0797-2

- About us. Tennessee Oncology. Accessed December 8, 2023. https://bit.ly/47Rs6V3

- Genetic testing and counseling resources. Cigna Healthcare. July 2016. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://shorturl.at/lortO

- Bilbrey LE, Dickson NR, Rao SK, et al. Partnership with an independent genetic counselor and standardized screening: effect on the identification, referral, and genetic testing of eligible patients in a community oncology clinic. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(suppl 27):138. doi:10.1200/JCO.2019.37.27_suppl.138