Oncology NEWS International

- Oncology NEWS International Vol 12 No 6

- Volume 12

- Issue 6

HPV Vaccine Trials Should Have Results by 2010

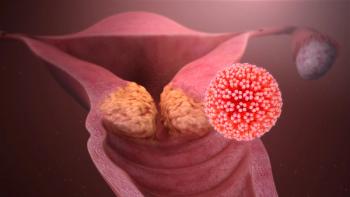

BETHESDA, Maryland-Two phase III studies involving tens of thousands of women should indicate before this decade’s end whether a vaccine aimed at preventing infection by two cancer-causing strains of human papillo-mavirus (HPV) will likely reduce the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer, and perhaps several other cancers as well.

BETHESDA, MarylandTwo phase III studies involving tens of thousands of women should indicate before this decade’s end whether a vaccine aimed at preventing infection by two cancer-causing strains of human papillo-mavirus (HPV) will likely reduce the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer, and perhaps several other cancers as well.

Merck & Co. has accrued more than 20,000 young women for its phase III study and continues to enroll participants in the United States, Latin America, and Asia. The study, which began late in 2001, is open to females age 16 to 26 who have not had an abnormal Pap smear and are HPV negative. The two principal investigators are Laura A. Koutsky, PhD, of the University of Washington, and Eliav Barr, MD, of Merck. The company also plans another phase III study of premenopausal women age 25 and older.

GlaxoSmithKline expects to begin a phase III trial of its HPV vaccine later this year, which will also take several years and involve thousands of women.

"What is actually being done is to try to prevent persistent infection by the virus that causes cervical cancer," said Douglas R. Lowy, MD, chief of the National Cancer Institute’s Laboratories of Basic Research and Cellular Oncology, addressing an institute-sponsored science writer’s symposium. "A reduction in cervical cancer will take many years. A reduction in incidence based on infection and abnormal cytology, however, will occur sooner. The younger the age of the population targeted for vaccination, the longer the interval before the effects on HPV infection will be seen."

Both the ongoing Merck study and the forthcoming GlaxoSmithKline trial have the same two primary endpoints, Dr. Lowy said: a reduced incidence of persistent HPV infection and a reduced incidence of moderate- and high-grade dysplasia.

The key to developing HPV vaccines came with the discovery that a structural protein of the virus, called L1, can self-assemble to form virus-like particles (VLPs) when its gene is expressed in a cell. "They look very similar morphologically to infectious particles, but they don’t contain DNA. L1 is also highly immunogenic," Dr. Lowy said.

During the early 1990s, there was an intense research effort focusing on HPV. Several institutions, including the NCI and the laboratories of the University of Queensland in Australia, made notable discoveries that opened up new areas of research and development.

Both Merck and GlaxoSmithKline have licenses under certain patent rights from the NCI as well as from other companies and institutions. Both HPV vaccines include VLPs of the HPV-16 and HPV-18 strains. In addition, the Merck vaccine also includes VLPs of HPV-6 and HPV-11, which cause genital warts.

Last year, Dr. Koutsky, Dr. Barr, and their colleagues reported 2-year results from an ongoing randomized phase II trial of a Merck vaccine that contained only HPV-16 VLPs. The preliminary analysis was prespecified in the trial protocol.

The study, which appeared in the November 21, 2002, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, involved 2,392 females, ages 16 to 23, who were randomized to receive three doses of the vaccine or placebo and followed for a median of 17.4 months. All of the women were HPV negative at enrollment.

Protection Rate of 91%

The team reported 27 transient HPV-16 infections in the placebo arm and 6 in the vaccinated group. Forty-one of the women receiving placebo developed persistent HPV-16 infections vs none of the women getting the vaccine. The total incidence of infection68 in the placebo group and 6 in the vaccine armand the finding of 9 HPV-associated cytologic abnormalities in the placebo women but none in vaccine group suggest a protection rate against HPV-16 of at least 91%, Dr. Lowy said.

The researchers themselves concluded that the vaccine "reduced the incidence of both HPV-16 infection and HPV-16-related cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)."

Effect on Pap Test Screening

The potential for a vaccine effective in preventing cervical cancers has raised several significant issues. "One important question is whether clinical screening programs should be modified in the HPV vaccine era," Dr. Lowy said.

An effective vaccine should significantly decrease the number of abnormal Pap tests and, thus, the need for follow-up studies, which together are estimated to cost over $5 billion a year in the United States. Such a vaccine should also reduce the number of cervical cancer cases in women who do not get regular Pap smears, which would prove a huge benefit in developing countries where cervical cancer is often the leading or second leading cause of cancer death among women.

Ending regular Pap tests after the introduction of an HPV vaccine, however, could have severe consequences. "If we had an HPV vaccine and no cervical cancer screening, it would actually save fewer lives in the United States than screening and no vaccine," Dr. Lowy said.

Using what he called "theoretical numbers" derived from existing data and what is known from early HPV vaccine work, he presented his analysis of why this would be true. "Assume that the Pap smear alone is 80% effective, and that all women are vaccinated, and the vaccine for HPV 16 and 18 is 90% effective and theoretically protects against 71% of cervical cancers," he said. "If nobody received cervical cancer screening and just got the vaccine, you would have a reduction in cervical cancer of 64%, compared to what we have now of 80%." Even if the HPV vaccine were 100% effective, he said, it would still protect against fewer cancers than screening.

He noted that screening plus vaccination would be better than either method alone. "Current screening plus all women being vaccinated would give you protection of an estimated 93%," he said.

Vaccinate Males?

A second question is whether to vaccinate both sexes or only females. Vaccinating males could reduce their risk of transmitting HPV to females. "However, I should point out that greater vaccine efficacy implies less of a need to vaccinate males, and as yet, there is no evidence of protection for males," Dr. Lowy said.

Articles in this issue

over 22 years ago

Low-Dose Chemotherapy Appears Promising in Pediatric PTLDover 22 years ago

Zoledronic Acid Reduces Skeletal Complications, Bone Painover 22 years ago

Cancer Control Efforts for Asian Americans Focus on West Coastover 22 years ago

Protein Patterns Identify Cancer and Assess Drug Efficacyover 22 years ago

New Salvage Regimen for Glioma Shows Promiseover 22 years ago

FDA Approves Velcade for Myelomaover 22 years ago

FDA Approves Iressa for Advanced NSCLC PatientsNewsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.