E. David Crawford, MD, serves as Series Editor for Clinical Quandaries. Dr. Crawford is Professor of Surgery, Urology, and Radiation Oncology, and Head of the Section of Urologic Oncology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine; Chairman of the Prostate Conditions Education Council; and a member of ONCOLOGY’s Editorial Board. If you have a case that you feel has particular educational value, illustrating important points in diagnosis or treatment, you may send the concept to Dr. Crawford at david.crawford@ucdenver.edu for consideration for a future installment of Clinical Quandaries.

Lymphoepithelioma-Like Carcinoma of the Urinary Bladder

A 65-year-old woman presented to a local emergency department complaining of right flank pain that had worsened over the past 10 days. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed intravesical tumors of the urinary bladder.

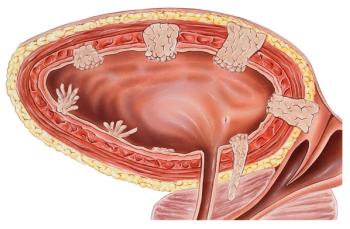

The Case: A 65-year-old woman presented to a local emergency department complaining of right flank pain that had worsened over the past 10 days. The patient also reported a 30-year history of intermittent gross hematuria. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed intravesical tumors of the urinary bladder. The patient elected to undergo a transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT); cystoscopic examination revealed multiple bladder tumors, with the largest and most aggressive appearing along the left anterior lateral wall and the right posterior lateral wall. Most of the tumor mass was resected, and histopathologic examination at an outside facility revealed a high-grade, urothelial carcinoma (UC) invasive into the muscularis propria. The original pathology was reviewed for a second opinion by a uropathologist (author FGLR) from our institution. The diagnosis was revised to superficial, high-grade UC papillary type (Figure 1) and associated lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC) of the urinary bladder, with extensive muscle invasion (pT2) (Figure 2). Immunostains for PAX8 and GATA3 antigens were positive in most of the tumor cell nuclei of the papillary component and in only 30% to 40% of the LELC component (Figure 3). The patient underwent a repeat TURBT at our institution; during the procedure, her entire bladder was found to be involved by a very large (9-cm) tumor. Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of LELC. During her staging workup, she developed a marked increase in bone pain. A positron emission tomography scan revealed widely metastatic disease with innumerable osseous metastases involving the axial and appendicular skeleton, many of which were lytic. The patient was subsequently treated to the right 9th rib, 8th thoracic vertebrae, and sternum with three-dimensional external beam radiotherapy (3D EBRT) to a dose of 20 Gy, given in five fractions. As her pain and performance status improved, she began chemotherapy with gemcitabine in combination with cisplatin.

Discussion

The majority of urinary bladder malignancies have a urothelial origin, accounting for approximately 90% of these tumors[1]; however, additional histological variants such as squamous, glandular, micropapillary, sarcomatoid, and other tumor types may be found. Because the tumor biology, specific therapy, and clinical prognoses of these variants are significantly different from each other, and from classic UC, an accurate histopathological diagnosis is required. LELC of the bladder was first described by Zukerberg et al in 1991.[2] It represents a rare variant of UC, with features resembling nasopharyngeal carcinomas (NC) and a reported incidence of 0.4%% to 1.3% of all bladder carcinomas.[3] Both LELC and NC are characterized by poorly differentiated carcinoma cells admixed with dense inflammatory cell infiltrates (Figures 2, 3); NC generally affects patients of Asian ancestry. Although histologically similar to NC, the pathogenesis of LELC tumors from other organs is not associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. In a literature review of LELC of the urinary tract from 1991 through 2012, all 35 cases reported were negative for EBV-encoded RNA by fluorescence in situ hybridization.[4] The pathogenesis, biology, and epidemiology of LELC from outside the nasopharynx are poorly understood,[5] but it has been proven that LELC arising from the bladder is of urothelial origin.[6] LELCs of the bladder harbor mutations of the p53 gene, correlating with the origin of this tumor. Due to the inflammatory cell infiltrate observed upon histologic examination, LELC may appear similar to a lymphoma or chronic inflammatory reaction, but cytokeratin stains reveal the presence of the carcinoma cells. LELC may be found admixed with classic UC cells, or less commonly, as a pure tumor type. The disease biology and clinical behavior of urothelial LELC have not been well established. Patients generally present with hematuria and are diagnosed at a more advanced stage of disease, with more than 50% presenting with at least T2 disease, as in the case study described here. In general, local therapy or partial cystectomy is not advised, owing to LELC’s propensity toward multifocality. However, LELC of the bladder is often thought to have an improved prognosis compared with that of UC.[3,7] Despite the tendency for muscle invasion with LELC, patients with predominantly LELC tumors have a disease-specific survival rate of up to 93%, with significantly worse survival outcomes in patients with classic UC mixed with LELC. In the present case, the UC was admixed with the LELC type, likely contributing to its rapid clinical progression. In the series of 27 cases reported from Johns Hopkins, 26% of the patients had metastases, and overall 5-year recurrence-free survival was 69%. Among the patients with localized disease treated with cystectomy, the rate of 5-year recurrence-free survival was 59%. In the patients with advanced stages of disease, few data are available regarding systemic therapy, but pure LELC may be more responsive to chemotherapy than conventional UC.[8] In general, standard cisplatin-based therapies have been used with satisfactory results.

Outcome of This Case

In the present case, the patient’s rapid clinical progression to bone-only sites suggests an aggressive pattern of progression in conjunction with a mixed histology. Thus far, the patient has responded well to radiation treatment and systemic chemotherapy, and she has experienced improved pain control.

Conclusion

Proper identification of histologic variants of UC is imperative to enable us to better understand the biology of these tumors and offer our patients tailored therapy. The development of clearer medical guidelines in this setting will be advanced by future studies of these rare subtypes that include molecular profiles, assessment of metastasis patterns, and evaluation of response to specific treatments.

Financial Disclosure:The authors have no significant financial interest or relationship with the manufacturers of any products or providers of any service mentioned in this article.

References:

1. Lopez-Beltran A, Cheng L. Histologic variants of urothelial carcinoma: differential diagnosis and clinical implications. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1371-88.

2. Zukerberg LR, Harris NL, Young RH. Carcinomas of the urinary bladder simulating malignant lymphoma. A report of five cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:569-76.

3. Porcaro AB, Gilioli E, Migliorini F, et al. Primary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the urinary bladder: report of one case with review and update of the literature after a pooled analysis of 43 patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2003;35:99-106.

4. Mori K, Ando T, Nomura T, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the bladder: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Urol. 2013;2013:356576. Available from:

5. Seisen T, Comperat E, Leon P, Roupret M. Impact of histological variants on the outcomes of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer after transurethral resection. Curr Opin Urol. 2014;24:524-31.

6. Williamson SR, Zhang S, Lopez-Beltran A, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the urinary bladder: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:474-83.

7. Amin MB, Ro JY, Lee KM, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:466-73.

8. Tamas EF, Nielsen ME, Schoenberg MP, Epstein JI. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the urinary tract: a clinicopathological study of 30 pure and mixed cases. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:828-34.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.