Synchronous Well-Differentiated Papillary Mesothelioma and Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma Arising From Endometriosis

Learn more about a 56-year-old woman diagnosed with well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma, and how she was diagnosed and properly treated.

Abstract

Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma (WDPM) is a rare mesothelial tumor of uncertain malignant potential. We present a unique case of a woman with synchronous WDPM and well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma (EA) arising from extraovarian endometriosis. A 56-year-old postmenopausal woman presented with a several-month history of right lower quadrant abdominal pain. She had a history of supracervical hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy secondary to endometriosis. Imaging reported a mass in the right lower quadrant originating from the distal ileum. At laparotomy, the patient underwent a right colectomy with resection of the terminal ileum and excision of a solitary peritoneal nodule. Pathology was consistent with a diagnosis of well-differentiated EA (arising from extraovarian endometriosis) and WDPM. Further treatment consisted of complete surgical staging/debulking and adjuvant chemotherapy directed toward metastatic well-differentiated EA. Surgeons should be familiar with WDPM as a potential finding in women of reproductive age undergoing abdominal surgery for any indication.

KEYWORDS: endometrioid adenocarcinoma, endometriosis, papillary mesothelioma, WDPM, debulking

Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma (WDPM) is a rare mesothelial tumor more commonly seen in the peritoneum of women of reproductive age. Extraperitoneal locations are uncommon. An association with mesothelioma has not been definitively established and its cause remains unknown. It is a tumor of uncertain malignant potential, and it is often found incidentally during laparotomy for other benign or malignant reasons.1-3

Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disease that affects approximately 10% of women of reproductive age. Malignant transformation of endometriosis occurs in approximately 0.7% to 2.5% of women. Up to 25% of endometriosis-associated malignancies (EAMs) are extraovarian and numerous cases have been reported in the intestines.4,5 Malignant extraovarian endometriosis is more common in women who are obese and postmenopausal who are taking estrogen replacement therapy.6 To the best of our knowledge, we present the first case of synchronous WDPM with well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma (EA) arising from extraovarian endometriosis.

Case Presentation

A 56-year-old postmenopausal woman presented with a 1-month history of right lower quadrant abdominal pain. There was associated diarrhea and weight loss of 25 lb over the past 5 months. Past medical history was significant for endometriosis. The patient had a supracervical hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy 25 years prior for endometriosis. She received hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for 4 years following surgery.

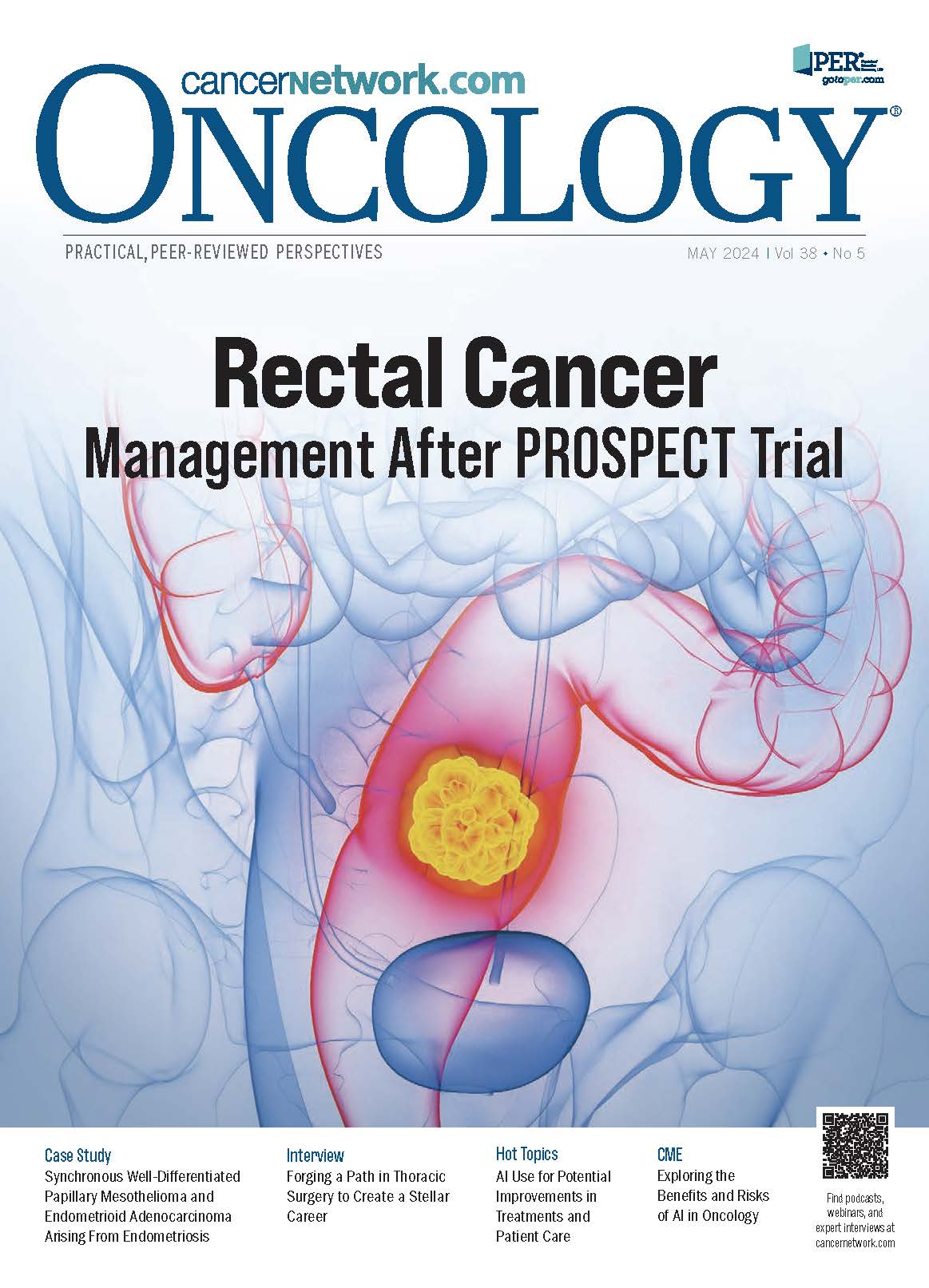

An initial CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a lobulated soft tissue mass in the right mid-pelvis likely originating from the distal ileum. The patient was referred to gastroenterology for a colonoscopy. Before the referral visit, the patient again presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain 1 month later. A repeat CT scan demonstrated a 4.9 × 3.6-cm right lower quadrant mass involving the distal ileum, with the potential for a neoplasm arising from the small bowel or within the right adnexa (Figure 1). A colonoscopy was performed and there was no mass noted in the distal ileum. The patient then underwent an exploratory laparotomy, extensive abdominal and pelvic lysis of adhesions, and a right colectomy with resection of the distal terminal ileum with primary anastomosis. An incidental solitary mesenteric implant was noted and was excised.

FIGURE 1: CT scan. Preoperative imaging demonstrated a right lower quadrant soft tissue mass concerning for neoplasm measuring 4.9 x 3.6 cm.

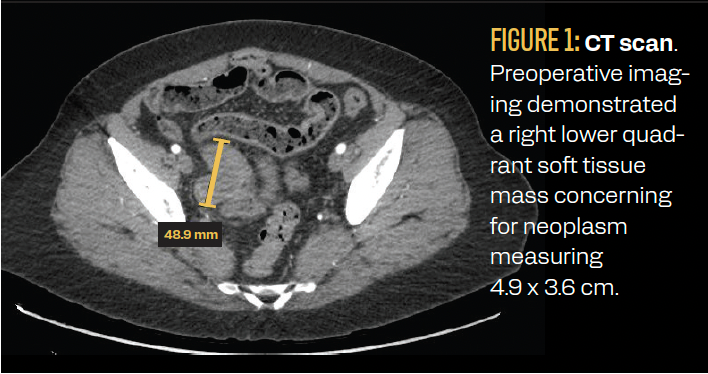

Histopathology of the right colectomy specimen demonstrated well-differentiated EA involving the wall of the terminal ileum

(Figure 2A). The mass consisted of neoplastic glandular proliferation with areas of squamoid differentiation (Figure 2B). There was no intrinsic mucosal abnormality in the ileum, appendix, or colon. Margins were free of tumor and 15 lymph nodes were negative for metastasis. The tumor stained positive for estrogen receptor and PAX8, with equivocal staining for GATA3, CK7, and CDX2 (Figures 2C and 2D).

FIGURE 2: Histopathology of right colectomy specimen. (A) The tumor invades the small bowel wall underlying the small intestinal mucosa (arrow). The tumor cells are arranged as back-to-back glands with little to no intervening stroma. There is associated necrosis within some of the tumor nests (×20 magnification) (B) The invasive tumor has a cribriform architecture composed of glands lined by columnar cells with round to elongated, pseudostratified nuclei and mild nuclear enlargement (×100 magnification) (C) Estrogen receptor is positive in the tumor glands, suggesting endometrioid adenocarcinoma (×100 magnification) (D) PAX8 is positive in the tumor glands, which is a marker of Müllerian origin and is positive in endometrioid adenocarcinoma (×100 magnification)

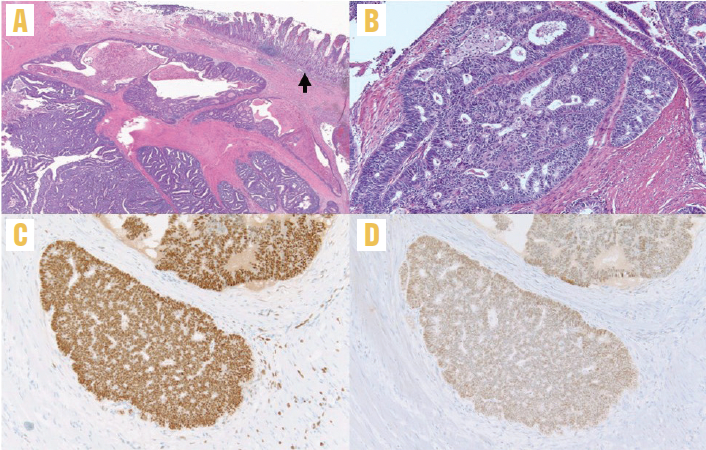

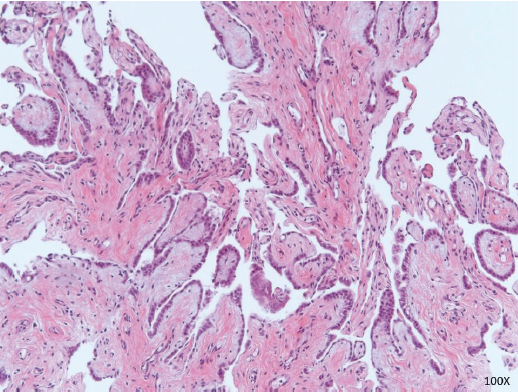

Stains were negative for CK20 and TTF1, consistent with a diagnosis of endometrioid carcinoma. Endometriosis was focally seen embedded within the wall of the ileum and colon, suggesting that the tumor arose in a background of endometriosis (Figure 3). The mesenteric implant demonstrated papillary mesothelial proliferation compatible with WDPM (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3: Endometriosis focally seen within the ileum and colon. There are focal isolated endometrial glands with pseudostratified nuclei and little to no endometrial stroma. These are dispersed as single glands and do not have the complex architecture of endometrioid adenocarcinoma, such as back-to-back glands with no intervening stroma or a cribriform architecture as is seen at the top of this image. In long-standing endometriosis, the endometrial stroma can become lost or attenuated as seen here. If there is no evidence of endometrioid adenocarcinoma within the uterus or adnexa of this patient, then it can be assumed that this adenocarcinoma arose from the endometriosis involving the bowel wall (100X magnification)

FIGURE 4: Papillary mesothelial proliferation. Papillary fronds lined by bland cuboidal mesothelial cells consistent with well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma. This is considered a tumor of uncertain malignant potential (×100 magnification)

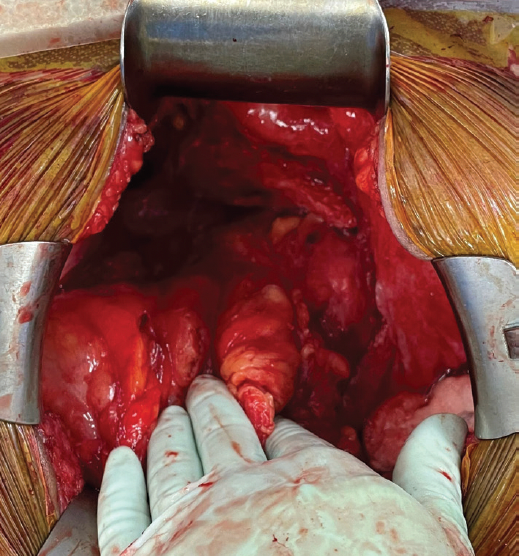

After a multidisciplinary tumor board discussion, a decision was made for surgical reexploration and staging/debulking, as warranted by intraoperative findings. Approximately 3 months after the initial surgery, the patient underwent staging/debulking including trachelectomy, bilateral ureterolysis, bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection, bilateral para-aortic lymph node sampling, partial right colectomy, and omentectomy. No gross residual disease was identified (Figure 5). All pathological specimens were negative for residual malignancy. The final stage was IIIC, grade 1 endometrioid carcinoma, best defined as primary peritoneal carcinoma, given that it arose from peritoneal endometriosis with a lack of a primary organ of origin. After surgical recovery, the patient initiated adjuvant systemic chemotherapy including carboplatin and paclitaxel as per standard guidelines for metastatic ovarian and endometrial endometrioid carcinomas.7 Due to estrogen receptor–positive histology arising from hormonally responsive endometriosis, endocrine maintenance therapy with an aromatase inhibitor is planned upon completion of chemotherapy.

FIGURE 5: Surgical debulking. No gross residual disease was identified following a thorough abdominal survey.

Discussion

Criteria for the pathological diagnosis of an endometriosis-associated tumor were originally defined by John A. Sampson, MD, in 1925.8 These criteria are (1) evidence of endometriosis near the tumor; (2) invasion from sources other than endometriosis excluded; and (3) the presence of tissue-like endometrial stroma surrounding characteristic epithelial glands. An additional criterion was added in 1953 to include histological evidence of benign endometriosis transitioning into malignant tissue.6,9,10 These criteria remain as the defining criteria for EAM and were demonstrated on histopathology in our case.

Primary EA is known to occur outside the endometrium, but EA arising from extragonadal endometriosis is rarely reported. Studies involving EAM have primarily focused on endometrioid and clear cell ovarian cancer, as the risk of ovarian cancer in patients with endometriosis is moderately increased.6,9,11 Malignant extragonadal endometriosis is more common in women who are obese and postmenopausal who are taking estrogen replacement therapy.6 Although our patient was obese and postmenopausal, she was not currently taking HRT and it is unknown whether she was prescribed combination or estrogen-only HRT after her hysterectomy. In this case, the ovaries were previously resected with no intraoperative evidence of ovarian remnant syndrome, and no normal ovarian tissue was identified on histopathology. Additionally, a trachelectomy was performed to rule out metastatic EA arising from residual lower uterine segment endometrium.

WDPM is an uncommon subtype of epithelioid mesothelioma with a benign course and a good prognosis.1-3 It is considered a tumor of uncertain malignant potential.1,12 As in our case, WDPM is pathologically described as a single layer of cuboidal mesothelial cells covered by thin papillary fronds.2,3 Management of WDPM is not standardized; however, complete surgical cytoreduction is recommended. Adjuvant chemotherapy is not recommended unless there is clear evidence of tumor progression or if complete excision is not possible.3,13

Malpica et al demonstrated that endometriosis is associated with WDPM in up to 23% of cases.1 However, the simultaneous occurrence of WDPM and endometrioid cancer is rare, with only 3 cases reported in the literature.14-16 WDPM was diffuse and was thought to be peritoneal carcinomatosis in 2 cases.14,16 One patient presented with abdominal bloating and ascites due to WDPM with endometrioid carcinoma as an incidental finding.15 To the best of our knowledge, we report the first case of synchronous WDPM and EA arising from extragonadal endometriosis, in this case arising in a patient with a history of a supracervical hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

Conclusion

We present a unique case of synchronous WDPM and endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from extraovarian endometriosis. WDPM is a tumor with uncertain malignant potential and its association with endometrioid carcinoma (of any organ site) is rarely reported in the literature. Complete surgical staging and debulking are recommended for both endometrioid adenocarcinoma and WDPM.

Corresponding author

Patrick Wagner, MD, MPH, FACS

patrick.wagner@ahn.org

References

- Malpica A, Sant’Ambrogio S, Deavers MT, Silva EG. Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma of the female peritoneum: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(1):117-127. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182354a79

- Butnor KJ, Sporn TA, Hammar SP, Roggli VL. Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(10):1304-1309. doi:10.1097/00000478-200110000-00012

- Daya D, Elliott McCaughey WT. Well‐differentiated papillary mesothelioma of the peritoneum. A clinicopathologic study of 22 cases. Cancer. 1990;65(2):292-296. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19900115)65:2<292::AID-CNCR2820650218>3.0.CO;2-W

- Yantiss RK, Clement PB, Young RH. Neoplastic and pre-neoplastic changes in gastrointestinal endometriosis: a study of 17 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(4):513-524. doi:10.1097/00000478-200004000-00005

- Slavin RE, Krum R, Dinh Van T. Endometriosis-associated intestinal tumors: a clinical and pathological study of 6 cases with a review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 2000;31(4):456-463. doi:10.1053/hp.2000.6712

- Gadducci A, Zannoni GF. Endometriosis-associated extraovarian malignancies: a challenging question for the clinician and the pathologist. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(5):2429-2438. doi:10.21873/anticanres.14212

- NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Uterine neoplasms, version 1.2023.

- Sampson J. Endometrial carcinoma of the ovary, arising in endometrial tissue in that organ. Arch Surg. 1925;10(1):1-72. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1925.01120100007001

- Krawczyk N, Banys-Paluchowski M, Schmidt D, Ulrich U, Fehm T. Endometriosis-associated malignancy. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016;76(2):176-181. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1558239

- Scott RB. Malignant Changes in Endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1953;2(3):283-289.

- Hermens M, van Altena AM, Velthuis I, et al. Endometrial cancer incidence in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(18):4592. doi:10.3390/cancers13184592

- McGinnis JM, Bloomfield V, Kazerouni H, Helpman L. Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma with two synchronous serous gynaecologic carcinomas in a 62-year-old woman: lessons learned for the gynaecologic surgeon. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2020;42(10):1262-1266. doi:10.1016/j.jogc.2019.12.012

- Nasit JG, Dhruva G. Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma of the peritoneum: a diagnostic dilemma on fine-needle aspiration cytology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;142(2):233-242. doi:10.1309/AJCPOTO9LBB4UKWC

- Rathi V, Hyde S, Newman M. Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma in association with endometrial carcinoma: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2010;54(suppl 5):793-797.

- Baykal C, Arioglu P, Gultekin M, Usubutun A, Ficicioglu C, Ayhan A. Well differentiated mesothelioma complicating endometrial carcinoma: a case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2006;27(2):200.

- Chen YY, Li PC, Hsu YH, Ding DC. Peritoneal well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma coexisting with endometrial adenocarcinoma mimicking peritoneal carcinomatosis: a case report. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;59(6):968-971. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2020.09.031