- ONCOLOGY Vol 27 No 7

- Volume 27

- Issue 7

Extended Surgery for Retroperitoneal Sarcoma: The Key to Maximizing the Potential for Cure and Survival

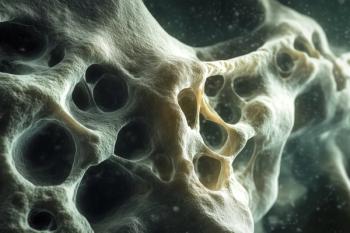

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for localized soft-tissue sarcoma (STS). It consists primarily of resection of the tumor along with a cuff of surrounding healthy tissue. In limb and trunk wall sarcomas, this basically implies resection of the surrounding soft tissues, which are mainly muscles, subcutaneous fat, and skin.[1] In the retroperitoneum, this necessarily should imply resection of adjacent viscera, even when they are not overtly involved.[2] This is the only way to avoid/minimize the presence of tumor cells at the cut surface (ie, positive microscopic surgical margins). Positive microscopic surgical margins are associated with a higher risk of local failure, distant metastases, and death.[3-6] Moreover, for STS located at critical sites, such as retroperitoneal sarcoma (RPS), positive surgical margins may have a direct impact on survival, favoring the development of inoperable local recurrences.[7] Indeed, unlike with STS arising in the extremities and trunk wall, local control in RPS poses a significant challenge and remains the leading cause of death, particularly in patients with low- to intermediate-grade tumors-roughly 75% of all cases.[8-13] Extending the resection to adjacent uninvolved viscera for primary RPS is the only way to minimize the presence of microscopic surgical margins and hence maximize the chance of cure. In essence, this strategy should often include ipsilateral nephrectomy and colectomy; locoregional peritonectomy and myomectomy (partial/total) of the muscle of the lateral/posterior abdominal wall (usually the psoas) (see Figure); splenectomy and left pancreatectomy, for tumors located on the left upper side; occasionally pancreaticoduodenectomy or hepatectomy, for tumors located on the right side; and vascular and bone resection only if vessels/bone are overtly infiltrated.[2]

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for localized soft-tissue sarcoma (STS). It consists primarily of resection of the tumor along with a cuff of surrounding healthy tissue. In limb and trunk wall sarcomas, this basically implies resection of the surrounding soft tissues, which are mainly muscles, subcutaneous fat, and skin.[1] In the retroperitoneum, this necessarily should imply resection of adjacent viscera, even when they are not overtly involved.[2] This is the only way to avoid/minimize the presence of tumor cells at the cut surface (ie, positive microscopic surgical margins). Positive microscopic surgical margins are associated with a higher risk of local failure, distant metastases, and death.[3-6] Moreover, for STS located at critical sites, such as retroperitoneal sarcoma (RPS), positive surgical margins may have a direct impact on survival, favoring the development of inoperable local recurrences.[7] Indeed, unlike with STS arising in the extremities and trunk wall, local control in RPS poses a significant challenge and remains the leading cause of death, particularly in patients with low- to intermediate-grade tumors-roughly 75% of all cases.[8-13] Extending the resection to adjacent uninvolved viscera for primary RPS is the only way to minimize the presence of microscopic surgical margins and hence maximize the chance of cure. In essence, this strategy should often include ipsilateral nephrectomy and colectomy; locoregional peritonectomy and myomectomy (partial/total) of the muscle of the lateral/posterior abdominal wall (usually the psoas) (see

Retrospective comparisons of series collected through prospectively maintained databases have shown in the past years how this approach in primary RPS translates to far better local control (roughly 80% vs 50% at 5 years)[14,15] and significantly better overall survival (roughly 70% vs 50% at 5 years).[16] Data on short- to medium-term morbidity have been provided, showing how, if conducted in tertiary centers by a team dedicated to this disease, these operations are safe, even when several surrounding organs are resected en bloc with the tumor.[17]

FIGURE

Right-Side Well-Differentiated Liposarcoma

In line with these results, microscopic infiltration of surrounding macroscopically uninvolved resected organs has been reported to be greater than 50%.[18] Similarly, when extended resections were proposed as re-excisions after a primary simple resection (with a postoperative CT scan apparently negative), the rate of residual tumor was shown to be as high as 80%.[15]

Although a formal comparison between simple excision and extended resection for primary RPS never has been attempted and never will be, taken together the data described above clearly favor extended resection as the reference standard approach to management of primary RPS. On the other hand, when a local recurrence has developed, there is no evidence to pursue such an approach.

That said, RPS is not a single disease.[19] There are at least four major well-characterized histological subtypes of RPS: well-differentiated liposarcoma (see

At this time, complete surgical clearance of RPS at the first operation remains the best therapy. Every attempt should be made to refer such patients to tertiary centers with the needed surgical oncology expertise, and where the disparate biological behaviors of the various histological subtypes can be accommodated in the overall therapeutic approach.

Financial Disclosure:The author has no significant financial interest or other relationship with the manufacturers of any products or providers of any service mentioned in this article.

References:

REFERENCES

1. Kawaguchi N, Ahmed AR, Matsumoto S, et al. The concept of curative margin in surgery for bone and soft tissue sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;419:165-72.

2. Bonvalot S, Raut CP, Pollock RE, et al. Technical considerations in surgery for retroperitoneal sarcomas: position paper from E-Surge, a master class in sarcoma surgery, and EORTC–STBSG. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2981-91.

3. Gronchi A, Casali PG, Mariani L, et al. Status of surgical margins and prognosis in adult soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities: a series of patients treated at a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:96-104.

4. Trovik CS, Bauer HCF, Alvegard TA, et al. Surgical margins, local recurrence and metastasis in soft tissue sarcomas: 599 surgically-treated patients from the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group register. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:710-16.

5. Zagars GK, Ballo MT, Pisters PWT, et al. Surgical margins and re-excision in the management of patients with soft tissue sarcoma using conservative surgery and radiation therapy. Cancer. 2003;97:2530-43.

6. Stojadinovic A, Leung DHY, Hoos A, et al. Analysis of the prognostic significance of microscopic margins in 2084 localized primary adult soft tissue sarcomas. Ann Surg. 2002;235:424-34.

7. Gronchi A, Lo Vullo S, Colombo C, et al. Extremity soft tissue sarcoma in a series of patients treated at a single institution: the local control directly impacts survival. Ann Surg. 2010;251:512-17.

8. Anaya DA, Lahat G, Wang X, et al. Establishing prognosis in retroperitoneal sarcoma: a new histology-based paradigm. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:667-75.

9. Strauss DC, Hayes AJ, Thway K, et al. Surgical management of primary retroperitoneal sarcoma. Br J Surg. 2010;101:520-3.

10. Lewis JJ, Leung D, Woodruff JM. Retroperitoneal soft-tissue sarcoma: analysis of 500 patients treated and followed at a single institution. Ann Surg. 1998;228:355-65.

11. Stoeckle E, Coindre JM, Bonvalot S, et al. Prognostic factors in retroperitoneal sarcoma: a multivariate analysis of a series of 165 patients of the French Cancer Center Federation Sarcoma Group. Cancer. 2001;92:359-68.

12. Hassan I, Park SZ, Donohue JH, et al. Operative management of primary retroperitoneal sarcomas: a reappraisal of an institutional experience. Ann Surg. 2004;239:244-50.

13. van Dalen T, Plooij JM, van Coevorden F, et al. Long-term prognosis of primary retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:234-8.

14. Bonvalot S, Rivoire M, Castaing M, et al. Primary retroperitoneal sarcomas: a multivariate analysis of surgical factors associated with local control. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:31-37.

15. Gronchi A, Lo Vullo S, Fiore M, et al. Aggressive surgical policies in a retrospectively reviewed single-institution case series of retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:24-30.

16. Gronchi A, Miceli R, Colombo C, et al. Frontline extended surgery is associated with improved survival in retroperitoneal low-intermediate grade soft tissue sarcomas. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1067-73.

17. Bonvalot S, Miceli R, Berselli M. Aggressive surgery in retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma carried out at high-volume centers is safe and is associated with improved local control. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1507-14.

18. Mussi C, Colombo P, Bertuzzi A, et al. Retroperitoneal sarcoma: is it time to change surgical policy? Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2136-42.

19. Gronchi A, Pollock RE. Quality of local treatments or biology of the tumor: which are the trump cards for loco-regional control of retroperitoneal sarcoma? Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2011-13.

Articles in this issue

over 12 years ago

Lymph Node–Positive Prostate Cancer: The Benefit of Local Therapyover 12 years ago

A Large Cystic Pancreatic Mass in a 45-Year-Old Femaleover 12 years ago

Two Paths Forward in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancerover 12 years ago

Can I Pray With You?Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.