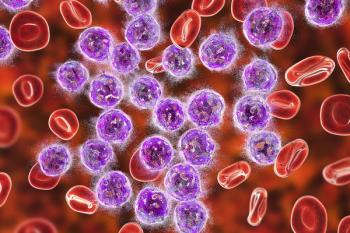

Inpatient Chemotherapy Is Appropriate for DLBCL

DLBCL patients who received in-hospital chemotherapy had a lower risk of death during hospitalization.

Administration of chemotherapy to patients hospitalized with diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) was associated with lower odds of death during hospitalization, according to the results of a study

The findings suggest that in this setting, most chemotherapy is given appropriately to non–critically ill patients,” wrote Anita J. Kumar, of Tufts Medical Center, and colleagues. The authors found that patients who were older or had longer durations of hospital stay had an increased risk for death.

“In a time of increased scrutiny of healthcare utilization, including aggressive measures during end-of-life care, we found that for chemotherapy administration for DLBCL is largely appropriate and given to patients who do not die during the same hospitalization,” the authors wrote.

According to the study, “chemotherapy for DLBCL can be given to inpatients in two scenarios: (1) planned admissions for patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed disease and (2) urgent unplanned chemotherapy for a newly diagnosed or acutely ill patient due to their lymphoma.”

Kumar and colleagues wanted to determine if certain patient or hospital characteristics were associated with increased likelihood of receiving inpatient chemotherapy and of death among this patient population.

The study was an analysis of data taken from the 2012–2013 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (HCUP-NIS) that identified patient and hospital characteristics associated with chemotherapy administration and death. The authors identified 11,150 patients diagnosed with DLBCL who were discharged from an inpatient setting from 2012 to 2013.

Chemotherapy was administered to about one-third of patients (29.2%). The patients who received chemotherapy were younger (P < .001), more often treated in urban teaching hospitals (P < .001), had fewer chronic conditions (P < .001), were more often male (P = .01), were more frequently covered by private insurance or Medicaid (P < .001), and were less likely to have an “extreme likelihood of dying” (P < .001). In addition, hospital visits where chemotherapy was administered were more expensive, but the duration of hospital stay was not significantly longer compared with patients who did not receive chemotherapy while hospitalized.

Patients who did not receive chemotherapy during admission were more likely to die compared with those who received chemotherapy (6.5% vs 2.3%; P < .001).

“We found that death during hospitalization was rare in this population,” the researchers wrote. “Patients who received chemotherapy had more than a 60% decreased odds of dying as those who did not receive chemotherapy, which suggests that chemotherapy admissions are more likely planned admissions in patients who are not acutely ill.”

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.