Nephrectomy, Hepatic Resection Possible Safe Aggressive Approach for RCC

Patients with RCC who underwent simultaneous nephrectomy and hepatic resection had similar postoperative mortality, long-term survival, and cancer-specific survival as those patients who underwent metastasectomy or en bloc resection of neighboring non-hepatic organs.

Patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) who underwent simultaneous nephrectomy and hepatic resection had similar postoperative mortality, long-term survival, and cancer-specific survival as those patients who underwent metastasectomy or en bloc resection of neighboring non-hepatic organs, according to the results of a single-center study

“Further analysis may help identify which patients will benefit most from synchronous hepatic resection,” wrote researcher Daniel D. Joyce, MD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, and colleagues. “Identifying specific patient characteristics that lead to poorer outcomes may help to create a selection criterion for which patients necessitate more aggressive surgical measures.”

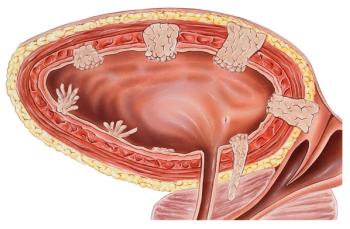

Approximately 25% to 30% of patients with RCC have metastatic disease at diagnosis, and the liver is the second most common site of metastases. Surgical resection involving neighboring organs is a standard of treatment in appropriately selected patients, according to the researchers.

In this study, Joyce and colleagues wanted to assess whether more aggressive surgical intervention for locally advanced or metastatic RCC to the liver was effective or associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

Looking from 1970 to 2009, the study compared 34 patients who underwent nephrectomy with hepatic resection for direct hepatic invasion (50%; n = 17) or metastatic RCC (62%; n = 21) with 68 patients who underwent nephrectomy and resection of non-hepatic locally invasive metastatic disease. The most commonly involved areas were the adrenal gland, muscle, bowel, and pancreas. Complete resection of metastatic disease occurred in 82% of patients with hepatic resection and 90% of the referent cohort.

Patients undergoing hepatic resection had higher intraoperative blood loss (1.6 L vs 1 L; P = .047). In addition, these patients had higher rates of post-operative deep vein thromboses (15% vs 1%; P = .02), “despite all patients being considered for our institution’s standard anticoagulation prophylaxis including early ambulation, sequential compression devices, and subcutaneous heparin injections,” the researchers wrote.

There were no significant differences in Clavien grade 3/4 complications or in perioperative mortality between the two groups.

During a median follow-up of 7 years, a majority of patients in both groups died. There was no significant difference in cancer-specific survival (1.5 years for hepatic vs 1 year for non-hepatic group) or overall survival (1.5 years for hepatic vs 0.9 years for non-hepatic) between the two groups.

“We acknowledge that the study population is modest and external validation is necessary; however, this study represents the only available series to-date that has attempted to control for the extent of resection of neighboring organs at the time of nephrectomy to ascertain the relative risk of hepatic cytoreductive surgery at the time of nephrectomy in RCC,” the researchers wrote.

Newsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.