Oncology NEWS International

- Oncology NEWS International Vol 16 No 10

- Volume 16

- Issue 10

Dr. Rai and the B cells; Dr. Chiorazzi and the B-cell receptors

Kanti Rai, MD, still remembers the life and quick death of a 3-year-old girl from Port Washington, Long Island, diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia. It was almost 50 years ago when he was chief resident in pediatrics at North Shore Hospital, Manhasset, New York. He was shaken to his core. His mentor, Arthur Sawitsky, MD, suggested that he might try research, which is easier on the heart.

Kanti Rai, MD, still remembers the life and quick death of a 3-year-old girl from Port Washington, Long Island, diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia. It was almost 50 years ago when he was chief resident in pediatrics at North Shore Hospital, Manhasset, New York. He was shaken to his core. His mentor, Arthur Sawitsky, MD, suggested that he might try research, which is easier on the heart.

And that is when he walked into the laboratory to try to figure out leukemia, and where he met a new breed of patients mostly older people who were either dying or living out their lives with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

By that time, he was working at the Brookhaven National Laboratory under the direction of Eugene Cronkite, MD. Dr. Rai remembers seeing three of Dr. Cronkite's patients: One who had CLL for 15 years and would show up for his annual exam in top form; another who was shuttled into the laboratory by wheelchair and only lived 1.5 years after his diagnosis; and the third who fell somewhere in the middle: He was sick but living for years with his symptoms.

Dr. Rai asked Dr. Cronkite, who was older and a full head taller, why there was such a difference in patients with the same disease. "That is for you to figure out, my boy," he said. And so it was that Dr. Rai asked for all the charts from every CLL patient seen at Brookhavenaround 80 patientsand tried to get a sense of the biology of the disease.

Staring at the wall

He made a table of each patient and pinned the tables up on the wall. And he stared. And stared. After a year or so of wall-watching with not much insight, he identified the 25 patients who were doing well and pinned their tables to one wall; those who were doing poorly or who had died were pinned on another; and on the final wall were the tables of the remaining patients.

"Suddenly," he said. "It hit me. The bone marrow of the people who died was completely compromised. They were all anemic, and their platelet counts were low. And these characteristics were there from the get-go, from the time of diagnosis." Indeed, those with normal levels were living longer. "The preservation of bone marrow became the key to predicting the amount of disease," he said.

Remember that this was before scientists knew much of anything about T cells or B cells. Soon after, CLL became known as a B-cell disease. In 1975, five years after the pin-up epiphany, Dr. Rai's findings were published in the journal Blood. By then, he was an oncologist at Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New Hyde Park (now part of the North Shore Health System in Manhasset), where he still practices in the Division of Hematology-Oncology, and things began falling into place for the disease and its patients.

His astute observations led to the Rai staging system of CLL, still used today. The Rai system takes into account the number of leukemic cells, platelet and red blood cell counts, and the extent and distribution of leukemia cell involvement of various organs.

The Rai staging system is used for classifying patients and making decisions on when to treat, but it does not predict precisely the clinical course of the disease. Prognostic markers are needed, especially to determine which patients are at higher risk and would benefit from early intervention.

New prognostic markers for CLL have emerged based on work by Dr. Rai and Nicholas Chiorazzi, MD, into the origins of the disease. Dr. Chiorazzi is director of the Laboratory of Experimental Immunology at North Shore's Feinstein Institute for Medical Research.

An accidental researcher

Like Dr. Rai, Dr. Chiorazzi ended up in CLL research somewhat by accident. After completing his medical training in the 1970s, he was set to follow a federal plan requiring physicians to go into military service. Six weeks before his Navy duty, he got a call saying they had enough doctors. He had a 2-year stay.

It was too late to start a practice of any standing, but Dr. Chiorazzi found a research fellowship at Harvard, and that is when he fell into the hands of immunologist Baruj Benacerraf, MD, who was instrumental in deciphering how B cells communicate with T cells. (In 1980, Dr. Benacerraf won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for unraveling the link between MHC genes and immunity.)

After his fellowship, Dr. Chiorazzi spent the next 11 years at The Rockefeller University studying B cells with another immunology giantDr. Henry Kunkel. By the time Dr. Chiorazzi moved to North Shore in 1987, he was already a B-cell expert. And he soon realized that studying CLL was an ideal way to unravel the inner workings of the immune system, since the basis of CLL is autoimmunization.

Understanding the CLL process

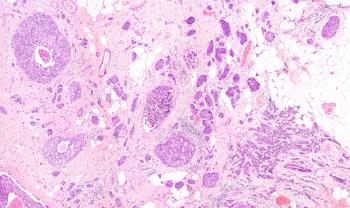

CLL cells are thought to originate from an overgrowth of B cells with polyreactive receptors shaped to bind multiple antigens, including autoantigens. Of note, the shape of the B-cell receptors of CLL cells is generally similar across CLL patients.

In the disease, the B cell gets stuck by endless stimulation and never carries out its intended job to create a specific antibody to fend off a particular invader.

In the last few years, Dr. Chiorazzi and his colleagues have figured out the structure of these B-cell receptors that trigger CLL and have sequenced the gene responsible for determining the shape of the rogue B-cell receptor. "We have come a long way," said Dr. Rai, who collaborates on the work.

With increased exposure to autoantigens via the polyreactive receptor, these B cells expand and convert to CLL cells that proliferate and avoid apoptosis. However, the progression of CLL may be slowed in patients with mutations of the immunoglobulin variable (V) region gene. These mutations alter the structure of the B-cell receptors making them unable to bind to the stimulating antigen. Indeed, studies show that CLL patients with V-gene mutations have a better prognosis than those with the unmutated gene.

"Immune system mutations are what you want," Dr. Chiorazzi explained. "It gives the body more possibilities to fight disease."

In addition to V-gene mutations, other prognostic factors under study by Drs. Chiorazzi and Rai include expression by the CLL cells of CD38 or the ZAP-70 protein (surrogates for V-gene mutations).

The scientists in Dr. Chiorazzi's lab now spend their days trying to identify substances that could alter the CLL process, such as agents that inhibit the B-cell receptor signaling pathway, block the antigen receptor, or target the actively proliferating CLL cells.

"The door to understanding and treating this disease is finally opening wide enough to begin to develop treatments to prevent or stop CLL," said Dr. Rai, who now sees upwards of 40 patients a week from all over the world.

Articles in this issue

over 18 years ago

Bill aims to 'revitalize' FDA by adding powers and databasesover 18 years ago

New myeloma trial results; two new studies initiatedover 18 years ago

Neoadjuvant trastuzumab increases pCR ratesover 18 years ago

Court rejects right of terminally ill to unproven drugsover 18 years ago

Sorafenib improves overall survival in Asian HCC ptsover 18 years ago

Skipping tam doses increases risk of deathover 18 years ago

The SGR: The madness behind physician payment fee cutsover 18 years ago

Dr. Pegram seeks new breast cancer challenges at Miamiover 18 years ago

SearchMedica.com receives awardNewsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.