- ONCOLOGY Vol 21 No 5

- Volume 21

- Issue 5

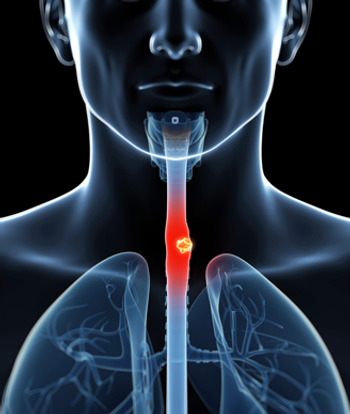

The Emerging Epidemic of Gastroesophageal Cancers: A Neglected Volcano?

Esophageal, gastroesophageal junction, and gastric cancers are underpublicized but are frequently lethal, and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinomas are increasingly common diseases in the United States and around the world. Although often grouped together in studies of chemotherapy, clear distinctions can be made in the locoregional therapy of these diseases. Esophageal squamous cell carcinomas may be treated with surgery or radiation with concurrent chemotherapy, whereas esophageal adenocarcinomas and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinomas are often treated with all three treatment modalities. Over the past several years, it has become increasingly evident that gastric cancer is a disease that is potentially sensitive to chemotherapy. In the perioperative setting—at least in the Western world—chemotherapy and sometimes radiation are applied. However, the optimal chemotherapy for advanced gastric or esophageal cancer remains unsettled, and there is no single standard regimen. Several new chemotherapy agents have demonstrated activity in these diseases, but the best chemotherapy remains to be determined. This paper will review the role of chemotherapy in gastroesophageal cancers.

Gastroesophageal adenocarcinomas (proximal gastric and lower esophageal or gastro-esophageal junction) are rapidly on the rise in both the West[1] and the developing world. The reasons may be diverse and still somewhat elusive, but for lower esophageal and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma, increasing body mass index of the Western population,[2] gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and consequent Barrett's metaplasia may be fueling the dramatic increase in younger American men (as well as, now, a noticeable increase in women).

Relative to the 1975 rates of incidence, these cancers have far surpassed the increases seen in prostate cancer or melanoma,[1] but who is paying attention? Apparently not the agencies that can make a big difference. The incidence of esophageal cancer has increased by 40% since 1990,[2] and most new cases prove to be adenocarcinoma on histology. We are not diagnosing these cancers early, and the associated mortality has continued to increase.[1] We project that this group of diseases will continue to rise over the next 20 yearsa volcano waiting to explodeand yet, we in the oncology community are not preparing ourselves to face the emerging epidemic.

In this issue of

ONCOLOGY

, Hwang has written a concise and balanced review of the current status of therapy for gastroesophageal cancers, drawing our attention to the seriousness of this problem globally and in the United States. His review is a welcome addition to the literature, and we appreciate this opportunity to comment on the subject. We will refrain from repeating the considerable details that Hwang has presented on many aspects of these cancers, and instead offer other comments that might be helpful to individuals interested in these diseases.

Prevention and Early Detection

There are two aspects to be considered in dealing with gastroesophageal cancers: early detection/prevention and therapy of established malignancies (localized and metastatic). In terms of prevention, nothing solid has been established for gastric cancer, apart from treating Helicobacter pylori when it is found. This measure may help only to some extent in at-risk populations. Clearly, there is nothing to lean on for the prevention of esophageal cancers.

Early detection of gastric cancer is practiced effectively in Japan and it is in early stages of development in Korea, but no strategy has been established elsewhere. Individuals suffering from GERD have a limited awareness of the need for early detection of esophageal cancer, but GERD and Barrett's metaplasia are not in the general public's vocabulary. (They should be.) Confusing and contradicting guidelines exist for surveillance of patients with Barrett's metaplasia.[3] The only thing everyone is clear about in this setting is when a patient is diagnosed with high-grade dysplasia. In the midst of all this confusion, we are left with late diagnoses of gastroesophageal cancers with nearly half of the patients having an unresectable (and, therefore, incurable) cancer.

Advanced Disease

For patients with advanced gastroesophageal cancers, the experience can be a struggle. These patients already have considerable baseline symptoms, poor tolerance to intensive therapies, deteriorating quality of life, and short survival. Few therapies have emerged. Few randomized trials have been conducted. Considerably more advances are needed. It would be important to develop therapies that prolong overall survival (beyond 12 months on a consistent basis) for patients with advanced cancer, have a favorable safety profile, and are convenientparticularly for patients but also for the medical team (ie, much less labor-intensive and cost-intensive). In addition, such treatment should maintain or improve quality of life and improve clinical benefit.

We do not believe this is a dream. With the advent of effective newer agents (for example, S-1[4] and biologic agents[5-7]), these benchmarks may be right around the corner. Future challenges will include the selection of optimum therapies and avoidance of ineffective ones, which may require considerable investigation of cancer biology and patient genetics.

For now, we urge greater efforts in early detection and prevention. For later stages of gastroesophageal cancer, we advocate the launching of more phase III trials. We need trials that are well-designed, large, and well executed, asking relevant but simple questions. Hwang has captured the spirit of the work that lies ahead of us.

Putao Cen, MD

Jaffer A. Ajani, MD

Disclosures:

Dr. Ajani has received grant support from Ascenta, Sanofi-Aventis, and Taiho; and lectures (no honorarium) for Amgen.

References:

1. Pohl H, Welch HG: The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst 97:142-146, 2005.

2. American Cancer Society website. Available at

3. Bresalier R: Barrett's metaplasia: Defining the problem. Semin Oncol 32:21-24, 2005.

4. Lenz HJ, Lee FC, Haller DG, et al: Extended safety and efficacy data on S-1 plus cisplatin in patients with untreated, advanced gastric carcinoma in a multicenter phase II trial. Cancer 109:33-40, 2007.

5. Dragovich T, McCoy S, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, et al: Phase II trial of erlotinib in gastroesophageal junction and gastric adenocarcinomas: SWOG 0127. J Clin Oncol 24:4922-4927, 2006.

6. Shah MA, Ramanathan RK, Ilson DH, et al: Multicenter phase II study of irinotecan, cisplatin, and bevacizumab in patients with metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 24:5201-5206, 2006.

7. Ocean AJ, Schnoll-Sussman F, Keresztes R, et al: Phase II study of PS-341 (bortezomib) with or without irinotecan in patients with advanced gastric adenocarcinoma (abstract 14040). J Clin Oncol 24(18S):627s, 2006.

Articles in this issue

almost 19 years ago

CDC Finalizes Advisory Panel Reccommendations for HPV Vaccinealmost 19 years ago

Study Finds Most Fentanyl 'Lollipop' Prescriptions Are Off-Labelalmost 19 years ago

Gynecologic Cancer Survivors: A Comprehensive Approachalmost 19 years ago

Treating Metastatic Colorectal Cancer While Questions Remain Unansweredalmost 19 years ago

Active Lifestyle Reduces Risk of Invasive Breast Canceralmost 19 years ago

Crossing the Quality Chasmalmost 19 years ago

Palliation of Colorectal Cancer: New Possibilities and ChallengesNewsletter

Stay up to date on recent advances in the multidisciplinary approach to cancer.